Dinah, ClinkShrink, & Roy produce Shrink Rap: a blog by Psychiatrists for Psychiatrists, interested bystanders are also welcome. A place to talk; no one has to listen.

Showing posts with label transference. Show all posts

Showing posts with label transference. Show all posts

Sunday, August 12, 2012

What Kind of Work is it I Do, Anyway?

I'm blogging during the closing ceremonies for the London Olympics. As if there's not enough stimulation going on here....

In Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work, we talk about psychotherapy as a process that occurs over time where the talking is an integral part of the actual treatment; that is, it's the talking itself that facilitates the cure. Traditionally, psychotherapy happens on at least a weekly basis -- sometimes twice a week -- and for psychoanalysis 3-5 times/week. Sessions are 50 minutes long and patients are often seen at a set time, for example, every Friday at 1pm.

I think of myself as a psychotherapist because I see the majority of my patients for 50 minute sessions and people generally tell me about the events going on in their lives. Unless someone is acutely symptomatic, very little of the sessions are devoted to symptoms, side effects, and medications, though certainly that is part of what gets discussed if there is a problem. The assumption, however, is that there is more to the psychiatric treatment I'm doing then checklists of symptoms and medication adjustments that take place in a vacuum that does not include the patient's life events, past events (including childhood) and their emotional reactions to their world.

Okay, so several readers and Amazon reviewers have commented on typographical errors in my e- novel, Home Inspection. I recently got the paperback proof back, and with the help of one of our readers, I've been re-reading it and going through the novel trying to see the words (and errors) my eyes (now on their zillionth reading) tend to simply not see.

For those of you who haven't read Home Inspection, it's a story told by a psychiatrist through the sessions of two of his patients. Dr. Julius Strand's life is a bit of a disaster: he continues to mourn the death of his first wife, his second wife kicked him out, he's living with his cat in an apartment full of unpacked boxes, his career has a crisis, his health is not good, and his relationship with his daughters is strained. Patient Tom is a cardiologist who is having panic attacks as he starts building his dream house with a woman who is certainly not his dream woman, and Patient Polly feels 'stuck' in her life. She struggles in her relationship with the psychiatrist and talks about her past begrudgingly, asking repeatedly if it will set her free if she talks about those past secrets. Through a series of coincidences, their paths all cross, and somehow, the patients help to cure the doctor.

The therapy that Dr. Strand does is a very conventional, psychoanalytically-informed therapy. His patients come at the same time each week. They talk about how past events inform their current behavior, and he thinks a great deal about how their relationships with him are relevant.

It occurred to me as I was reading my own account of treatment (fictional though it may be), that I don't do really do this type of therapy anymore. I'm not sure I ever did. When people start therapy and are feeling badly, they generally come weekly, but as soon as a patient's symptoms get better -- often a matter of weeks to months -- they ask to come less often, and most patients come every two to four weeks. Some I see on an irregular basis -- they call when they have a problem and want to come talk. Therapy is expensive, and in our harried world, most people don't have either the time, money, or inclination for sessions once or twice a week. While there are people I tend to see on specific days or at specific times, most patients don't have a fixed regular session -- I think this is because I like having some flexibility to my schedule. And while people do talk about what is going on in their lives, and I often will ask about how past events and emotions have impacted them, I don't spend much time focusing on the therapeutic relationship. I won't say never -- and certainly, the fictional Dr. Strand thought about it much more than he talked about it -- but it is not a major focus of treatment for most people.

So I think of myself as a psychotherapist, and I think of psychotherapy as a crucial part of treatment, but if I don't see most people for weekly sessions, then what exactly is it I do?

And if you don't feel like talking about psychotherapy, by all means, tell me what you think of the closing ceremonies!

Monday, March 05, 2012

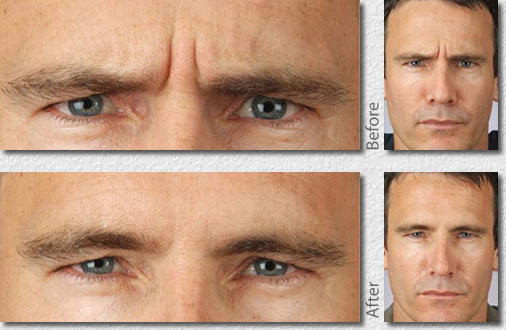

Does Botox Change The Shrink?

So I'm a little older than I used to be and recently when I look in the mirror, I've noticed some lines in my forehead when I make specific expressions. I'm not so sure I like them; when they show up in photos, they definitely make me look older. And yet, I know that these lines aren't just from aging, they are an occupational hazard. Part of attentive listening in psychotherapy involves using your face to convey, in non-verbal ways, obviously, feelings and expressions and interest and even questions. These are my quizzical lines. Really? Don't you think you're kidding yourself there? Give me a break. Not a word gets uttered, but oh so much gets communicated in silence, with the movement of just a few muscles. Yes, Clink, here and there I have a moment of silence. A short moment, but still. Wrinkles as an occupational hazard.

Every now and then I have the thought that maybe I should Botox those lines away, but my first thought is always, will it interfere with my work? Who am I as a psychiatrist without the Quizzical Look? Will my patients relate to me differently? Will they have worse/different/better therapeutic outcomes if my facial muscles are paralyzed? Oh, and since they came from my work, can I tax deduct the cost of botox treatments?

No worries, I'll stay wrinkled....or quizzical....as long as Clink continues to be a nun look-a-like and Roy remains a geek.

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Missed Opportunities?

Before I begin, I wanted to let you know that ClinkShrink wrote a post called Can You Tame Wild Women? over on our Shrink Rap News blog this week.

____________________________

When we talk about psychotherapy, one aspect of what we look at is the process of what occurs in the therapeutic relationship. This is an important part of psychodynamic-based psychotherapy, meaning psychotherapy that is derived from the theories put forth by Freud. Psychoanalysis (the purest form of psychodynamic psychotherapy) includes an emphasis on events that occurred during childhood, and a focus on understanding what goes on in the relationship between the therapist and the patient, including the transference and counter-transference.

In some of our posts, our friend Jesse has commented about how it's important to understand what transpires in the mind of the patient when certain things are said and done. Let me tell you that Jesse is a wonderful psychiatrist, he is warm and caring and attentive and gentle, and he's had extensive training in the analytic method, he's on my list of who I go to when I need help, so while I want to discuss this concept, I don't want anyone, especially Jesse, to think I don't respect him. With that disclaimer.....

On my tongue-in-cheek post on What to Get Your Psychiatrist for the Holidays, Jesse wrote:

When I say the Shrink should look at the context, even in small matters a gift might come with a subtext: "I just told you some terrible things about me and I want to be sure you still like me." It can be a bribe. It can be a seduction. It can simply be a gift given out of gratitude. The important concept is that we think about everything. Unlike a physical examination done by an internist, everything that occurs might be some window into how we can help the patient, and we do not want to lose that opportunity.

So wait, the patient comes to me because he symptoms of a mental disorder, often depression or anxiety, or problems controlling his behavior, or he's overwhelmed with stress and isn't coping well. Why is it so important that we understand every aspect of the sub-texted interactions? How does this cure mental illness? Why is it bad to accept (or not) a gift and move on? Why do we have to think about everything? And if it's really important, won't it come up again? Is it really crucial that we not lose that opportunity? Maybe I just want to take the cookies and say 'thank you' because

Just so everyone knows that I am still Jesse's friend, I am posting the video he sent me of his late grand-chinchilla, Chinstrap. And yes, Jesse had a grand-chinchilla. He does assure me that Chinstrap was having a good time in this video, because I wondered.

And I'd like to thank Steve over at Thought Broadcast for providing the graphic for today's post.

____________________________

When we talk about psychotherapy, one aspect of what we look at is the process of what occurs in the therapeutic relationship. This is an important part of psychodynamic-based psychotherapy, meaning psychotherapy that is derived from the theories put forth by Freud. Psychoanalysis (the purest form of psychodynamic psychotherapy) includes an emphasis on events that occurred during childhood, and a focus on understanding what goes on in the relationship between the therapist and the patient, including the transference and counter-transference.

In some of our posts, our friend Jesse has commented about how it's important to understand what transpires in the mind of the patient when certain things are said and done. Let me tell you that Jesse is a wonderful psychiatrist, he is warm and caring and attentive and gentle, and he's had extensive training in the analytic method, he's on my list of who I go to when I need help, so while I want to discuss this concept, I don't want anyone, especially Jesse, to think I don't respect him. With that disclaimer.....

On my tongue-in-cheek post on What to Get Your Psychiatrist for the Holidays, Jesse wrote:

When I say the Shrink should look at the context, even in small matters a gift might come with a subtext: "I just told you some terrible things about me and I want to be sure you still like me." It can be a bribe. It can be a seduction. It can simply be a gift given out of gratitude. The important concept is that we think about everything. Unlike a physical examination done by an internist, everything that occurs might be some window into how we can help the patient, and we do not want to lose that opportunity.

So wait, the patient comes to me because he symptoms of a mental disorder, often depression or anxiety, or problems controlling his behavior, or he's overwhelmed with stress and isn't coping well. Why is it so important that we understand every aspect of the sub-texted interactions? How does this cure mental illness? Why is it bad to accept (or not) a gift and move on? Why do we have to think about everything? And if it's really important, won't it come up again? Is it really crucial that we not lose that opportunity? Maybe I just want to take the cookies and say 'thank you' because

- A) I don't want to hurt my patient's feelings,

- B) it can be difficult to look at the meaning without upsetting the patient or putting the patient on the defensive and so the patient has to be fully on-board for this type of therapy and those patients generally don't bring gifts (ah, maybe we should be asking all analytic patients why they didn't bring gifts, now that might yield interesting information), and

- C) I like cookies.

Just so everyone knows that I am still Jesse's friend, I am posting the video he sent me of his late grand-chinchilla, Chinstrap. And yes, Jesse had a grand-chinchilla. He does assure me that Chinstrap was having a good time in this video, because I wondered.

And I'd like to thank Steve over at Thought Broadcast for providing the graphic for today's post.

Labels:

pets,

psychodynamics,

psychotherapy,

transference

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Transference to the Blog, Revisited

Early on in Shrink Rap life, I wrote a post called Transference to the Blog. A bit tongue-in-cheek but it was inspired by the idea that readers seemed to have their own feelings and internal relationships with Shrink Rap, just as we had with them --so Counter-transference emanating from the blog was also addressed. As was transference to the duck.

Over the years, the feelings and tone in the comment section of Shrink Rap has varied quite a bit. At times it's warm and fuzzy with people writing in to tell their own stories-- good and bad-- and readers offering one and other support. At other times, it's been rather hostile with reader writing in to express their venom toward psychiatry and to criticize other commenters who say they have benefited from treatment. From my perspective, I thought things had calmed down, at least a bit, but we've gotten several communications from readers complaining they feel attacked if they make comments. I worry that our continued commenter-constituent base of those who criticize the field has served to silence those who might like to have a voice. Even my co-bloggers seem to have lost interest in engaging in these conversations.

Some of the commenters have asked why people return to make the same points over and over. What interest is there in this drum beat of reiteration after reiteration of why psychiatry is bad. I've wondered the same thing, and wondered why they don't form their own blog! If you're a Republican, don't you frequent Republican blogs? Why hang out and hound the Democrats? Do Jewish people standout side Catholic Churches to make the point that the Catholics are wrong in their beliefs? Which brings me to the subject of Transference to the Blog. Obviously, I can't speak to the motivations of people I don't know, but I am allowed to speculate in my head, and I can't help but assume that those who visit with a repeated agenda that opposes the spirit of by-psychiatrists-for-psychiatrists (and anyone else who might enjoy the ride), do so because they've had a bad experience and Shrink Rap might serve the purpose of being a flame to the metaphorical moth. It feels like a compulsion to revisit the site of a trauma in the hopes of mastering it. Sorry if this is too shrinky for you, but oh, hey, I'm a psychiatrist and we do sometimes think this way.

When people make the same adversarial comments over and over, it gets old and it stifles new ideas and new discussions.

If you believe that psychiatrists wrong patients by inflicting diagnoses on them, that it's wrong to take medications for psychiatric problems or psychic distress, that psychiatrists have evil motives, that psychiatric disorders do not exist, that psychiatric hospitals inflict damage, that involuntary hospitalization is never, ever, warranted no matter how sick or how dangerous someone is, or that psychiatry is about inflicting punishment/being coercive & controlling, and not about healing or treatment, then please know we have heard you. You're welcome to your views, but the writers of Shrink Rap don't agree that these are over-riding themes in psychiatry as a whole, and expressing the same opinion and rationale for the 27th time is not going to change this. On the other hand, it does appear to offend many people who might like the opportunity to comment, express themselves without a barrage of insults, and garner either support or similar stories in a welcoming environment.

This may be read as Don't Criticize Psychiatry. Read it as you wish. I don't think we've ever steered readers away from an honest look at the issues, or that we defend every aspect of our work as done by all of our colleagues. Our book is about psychiatry with the good and the bad, and we mostly discuss it in positive terms with the hope that this will set the standard : Hey, none of the docs in Shrink Rap are prescribing medications after 10 minute evaluations, they all listen to their patients and have thoughtful discussions-- maybe that's what I should expect.

If you've made your point, it's been made. If you have a new point and it critiques psychiatry in a new way, please say it in a manner that is respectful of those who may be struggling.

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Guest Blogger Jesse: When Patients Don't Pay

Dinah asked that I “blog on what you do when patients don't pay.” I’ll try to put that question in a larger context. If a patient is seeing a physician for treatment of a mole, or of a fever, the treatment of those illnesses has no relation nor is affected by when or how the doctor is paid (other, of course, that the doctor might refuse to treat the patient). In psychodynamic therapy, where the therapist is helping the patient with relationships, anxieties, attitudes, and conflicts, everything that occurs is potentially helpful if it is understood. Observing and thinking about actions and feelings is a part of the treatment, as important a tool to the therapist as a stethoscope to a cardiologist.

Money is something loaded with meaning to most people. What does it mean that the patient forgets to pay? Does it mean “if you really cared about me you would not charge me”? Is it a reflection of anger for something that occurred in the last session? Is it a displacement of feelings from something else (“my boss didn’t give me the raise I expected”)? Is it completely inadvertent (Freud famously said “Sometimes a cigar is only a cigar”)?

There are so many possibilities, and the psychodynamic therapist wants to understand them. How the patient relates to the therapist is some part of how he relates to others. The patient hopefully starts to watch his own actions and attitudes, and also tries to understand them. A nonjudgmental stance helps the patient do this.

The therapist himself needs to be comfortable dealing with the subject of money. Sometimes beginning physicians fluctuate between feeling they are too inexperienced to be paid and feeling that they deserve anything they ask. We physicians might even (unfortunately) take on the attitudes of the insurance companies themselves (“Identification with the Aggressor”).

There are times when the treatment needs to be discontinued, or the patient referred for other care. Clearly, if the therapist has allowed a patient to go a long time without paying, without good reason thoughtfully discussed, both doctor and patient have unwittingly colluded in avoiding very important issues.

Many therapists believe it is important for the patient to pay something, regardless of his economic state. It is part of the patient’s self-esteem. It indicates a professional relationship, one in which the patient essentially is employing the therapist (physician, lawyer, accountant, et al) and in which the therapist has professional obligations to the patient. It is therefore part of the professional boundaries.

There is a curative aspect to the attitude I’m describing. To the extent that the patient can increase his ability to examine his own actions and feelings in a nonjudgmental manner he gains control over areas of life which may have been becoming increasingly difficult for him.

What have others experienced in this regard, and how do you think of these issues?

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

How Do You Switch Docs?

We got a very thought-provoking question:

I was wondering if you could address the issue of switching from a long standing psychiatrist (who provides regular psychotherapy - the ideal which garnered so much controversy in one of your other posts!) following a scheduled medical leave because the covering doctor seemed to be a better fit. What sorts of issues could be involved in that? I know both parties are professional, but I would still be worried about hurting one's feelings. Or what if the covering doctor did not want to continue to see the person; would that then ruin a dynamic of going back to the original doctor? How can this even be addressed?

Wow. Where do I begin.

1) In a long-standing psychotherapy, one of the issues that might be addressed is the therapeutic relationship and how that plays out as a mirror of other relationships, a process known as transference. The question of what else is going on here should be addressed. Is switching doctors a way of avoiding a problem that should be examined? Is leaving adaptive or a way of not addressing an issue.

2) Sometimes in the course of the therapeutic relationship, we forget that the goal is the treatment of psychiatric disorders and the alleviation of symptoms. Before changing doctors it would be important to take stock: why did you go to treatment? What were the symptoms and difficulties, and how are they doing now. If you're doing better, then I don't think it makes sense to leave a treatment that has been helpful because someone else is an easier person to talk to or a better fit. The goal of treatment is to get better, not to find a good friend. This isn't to say that people don't feel helped by a comfortable therapeutic relationship: they do. It is to say Take Stock first.

3) If this is an insight-oriented psychotherapy with frequent sessions, honesty demands that you at least mention the fantasy of leaving to the old doctor. If it is not that type of treatment, you may want to call the covering doctor and have a brief discussion: Will she take you on? She may feel like she's stealing patients and that may not be cool with her. She may have no openings. She will likely say to discuss it with your old doc first. Before you actually leave the first doctor, it makes sense to have a phone conversation with the new doctor, or even a single one-time appointment to discuss why you want to change, whether she will see you, and if that makes sense. Are there insurance or fee issues? Can she see you at a time you are available? Since you're someone who's needed to see a covering doc, what are her policies on emergencies?

4) If you're not getting better with your first doctor and you've followed treatment recommendations and given it a long enough period of time, then switching doctors is reasonable. If you're worried about hurting someone's feelings, then hopefully it means there has been something positive in the relationship. It may be worth taking stock with your first doctor. These are things that have been helpful. This is why I'm thinking I may want to try seeing someone else. If there's nothing positive, then leave and see someone else, even if it's not the covering doc. If there are positive things, then point them out. If the doctor's feelings are hurt, they will live (I promise). It may not, however, make sense to return to someone you've fired if things don't go so well with the second doctor, and leaving may indeed include closing a door.

Thanks for the great question and I hope that was helpful.

Wednesday, October 06, 2010

My Friend, My Shrink

I just finished reading Dr. Gary Small's book, The Naked Lady Who Stood on Her Head. I talked about it during our podcast, and maybe, someday, that podcast will be posted.*

In the final chapter of the book, Dr. Small talks about his mentor, friend, and father-figure who has been mentioned throughout the book. The mentor approaches him on the golf course, where they meet to talk, and says he needs psychotherapy and Gary is the man to do it. The author is surprised, hesitant, and a bit uncomfortable with the demand (it comes as more than a request). His wife likens it to the need for a plumber or a dentist, and Dr. Small takes on the task. The mentor calls all the shots: where the meetings will be, what pastry they will eat, the form of his payment. The author initially misses the diagnosis and uses this as an example of how one can be blinded.

So is it okay for a friend to treat a friend?

I was in an institution where the resounding feeling is that psychiatric disorders are medical diseases like any other: the patient should go where the care is best. Obviously, our institution gave the best care, and so there was no taboo about faculty being treated (or even hospitalized) within the department. This is not to say that everyone treated their friends, but people might not move their care as far away as one might imagine (and sometimes people treated their friends).

At the same time, the standard professional boundaries suggest that friends should not treat friends, and that such arrangements are not kosher, especially after the fact if the treatment is called in to question.

Dr. Small talks about a delay in diagnosis. He doesn't talk about the fact that the patient here is dictating the care in a way we generally don't view as being helpfu to patients-- even VIP patients-- or that the desire to please authority figures can be very powerful.

------

* Regarding the My Three Shrinks podcast: We've decided that I, the non-geek, should try to produce the podcasts for the near future. Roy said he'd rather stick a fork in his eye than teach me to do this. Clink is trying, but even the process of transferring the recordings to my computer has been rough, not to mention that our podcast programs don't sync. Soon... we hope.

Labels:

book,

boundaries,

friendship,

psychotherapy,

transference

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Good Shrink. Bad Shrink.

Over time, I've noticed some trends among our blog commenters. Some readers comment on the content of our posts, others link us to Viagra spam, and finally, some readers talk directly to us. We hear about their own experiences of the topic we've blogged about, or simply about their day. This is good, though I could do with a little less Viagra or AirJordan spam in my life.

Sometimes readers inject enough of themselves into their comments that it becomes clear they have opinions about us, the Shrink Rappers, feet, ducks and all. Sometimes it seems like readers are poised to like us, and other times it feels like readers are lying in wait, looking to attack. I was particularly struck by the comments people made on my post about The Texting Shrink. Rachel says I have a kind-heart and another commenter (?--I think it was Retriever) noted that I do this to increase my availability to patients. Dr. Steve put it bluntly: I am idiot! I hope I do have a kind heart, but I text with patients because I've found this to be to my convenience--- it's a quicker way to deal handle brief messages, and none of it's about being more available. My life is better if I get a "stuck in traffic" text and know I have time to run to the restroom or eat a snack. And if a patient needs me to phone a pharmacy or return a call, it's so much quicker to click on the texted number than it is to re-listen to my messages and try to decipher that phone number 6 times by replaying voicemail -- and oh, I don't have a pen and can I memorize it quickly enough?.

Am I an idiot? I believe I've thought it through, but I may be.

The Texting Shrink was only one example. In our years of blogging, many posts have inspired strong reactions, and I've come to be very careful about my choice of words, especially when discussing medications. Sometimes it feels like no matter how gently I word things, someone is poised to simply say, psychiatry is bad, no one should see a shrink, no one should take psychotropic medications, all shrinks care about is money.

Some people think their psychiatrists don't care about them -- and for all I know, they may be right -- others believe their doctors think and care about them a lot, in a way that may not be realistic. Obviously, doctors think and care about their patients (oh, I hope), but docs are people with their own lives and problems.

I'm hoping for a happy medium somewhere. Like Dr. Steve says, I may be an idiot.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Who's It All About?

In my last post, You May Leave Now, an anonymous commenter talked about how his/her psychotherapist steers the conversation to looking at the therapeutic relationship. She asks the patient if he/she feels abandoned during vacations or rescheduled sessions. The patient says "No, I understand you've got a life," and feels dismissed when the therapist doesn't take this at face value and continues to drift back towards a discussion of feelings that are (or are not) arising in the therapeutic relationship.

In traditional psychoanalytic practices (or those influenced strongly by psychoanalytic thinking) the "analysis of the transference" is a central theme to treatment. It means looking at and understanding the relationship with the therapist as a way of understanding feelings the patient carries with him from past relationships that continue to play a part in his present concerns.

None of the Shrink Rappers are psychoanalysts-- so this is my disclaimer. I ramble, but it's not clear I really know what I'm talking about.

What do I think of this technique? I guess I think it's important in the realm of someone who is inclined to look at the relationship and who likes to think this way. Many of my patients come to see me because of problems with their moods or anxiety, and to focus the discussion on the therapeutic relationship often feels forced. The discussion described by Anonymous feels kind of forced. It's not one that I personally am always comfortable with--- it assumes a degree of narcissism by the therapist-- that everything comes back to this one particular relationship. It's also just an uncomfortable discussion for me, unless some version of distress/disappointment or concern about the relationship is brought up by the patient. But for the average patient talking about their work or their family, or their distressing symptoms, it feels a little weird to inject the idea that it's about the relationship.

Lots of things in medicine are a little weird. There are personal questions and all sorts of body parts being palpated and fluids being infused or withdrawn from the oddest of places. It's not about the usual interpersonal transactions. It's about diagnosing and healing. So if analyzing the transference is part of what cures illness, improves functioning, or makes life go smoother in anyway, then I'm all for it, even if it's a bit awkward.

I haven't fully brought myself to that place for a patient who isn't initiating (unless it's otherwise obvious that this is an issue). My sense is that probing into the patient's feelings for the therapist in a repeated and unwelcome way may put some people off or may foster a dependency that can then become it's own focus of treatment. In people with personality problems, sometimes this is necessary, but it's not usually fun. It puts a lot of pressure on the therapist-- it's much easier to call a vacation a vacation and not deal with at a major abandonment theme.

My sense is that for the average patient with a psychiatric problem, focusing on the therapeutic relationship in a major way probably does not make people better. I don't usually do it, and people still seem to heal.

Any thoughts?

Friday, December 19, 2008

Mutual Attraction Between Therapist and Patient

|

"Well, I am glad she finally got to Dr. Gabbard, because he is one smart guy. Still, I found her supervisor's reponse deeply disheartening and soulless - if not neutered.

Fact is, as everybody knows, humans are prone to affection, attraction and attachment and there is nothing necessarily different about whether that occurs in a shrink's office, or between a businessman and his secretary, teacher and student, clergyman and congregant, trainer and client, doctor and nurse, lawyer and client, classmates, or business associates and office colleagues. Romantic feelings in offices (like many other emotions) are ubiquitous. Sometimes it's mutual...

When you put people together, things of all sorts happen. Analysts and psychotherapists have the peculiar and challenging task of figuring those things out rather than acting on them."

She got help and referred the patient out, but I thought the post deserved attention so am linking it here. Interesting to read in the comments about the attempt to contact said psychiatrist, a Dr Lindsay Raymer at Baylor.

Thanks, Bird Dog.

Monday, May 19, 2008

Bah Humbug Transference

On my post called It's My Life, I'll Blog If I Want To, one commenter ( green tea) wrote:

I would have a really hard time if my therapist had a blog. It would make them seem too "human" too fallible. I think part of the illusion of therapy is that the person sitting across from us brings their BEST person into the room. In the blog, it's hard to maintain that sense of bounded distance. That detachment that invites a client inward, and into themselves. As an aside-- why use the word "transference" when "relationship" is more apt?

Green tea, I have to say that I agree with you. Here's the issue though: it would be wonderful if every therapist was a wonderful, infallible, highly moral, human being who lived life on a higher plane than the rest of us, and if, barring that, the therapist could keep all skeletons, failures, incorrect or unplanned emotional responses safely locked in the closet and out of sight of any patients.

Sometimes this is so important to a patient that the patient goes to lengths to find distance in therapy: maybe traveling to a distant city, paying in cash so that a psychiatric diagnosis won't come around to bite, making every effort to avoid information about a therapist's personal life/blogs/writings/friends, whatever.

Here's my question: Where's the Line? The real life reality is that therapists have issues, they can endorse unseemly political opinions, have messed up children, icky public divorces, dirty secrets that aren't so quiet. Who wants to know that their therapist hasn't spoken to his own mother in 23 years? Or that he's a member of a church that insists all non-members (including said patient) are condemned to an eternity in Hell? That he buys kinky things in porn shops? What about that prison tattoo? I could go on and on.

At what point does one's profession dictate who one has to be in one's private life? If you think you may want to run for President or for the Supreme Court, well....we all want you to be perfect: pick your pastor wisely, don't inhale, never never never pay your nanny under-the-table, declare everything, deduct nothing, watch where you put that cigar, and don't have ECT. Try not to shoot the neighbors, even by accident.

If you're a psychiatrist, some things are clear: you can't be impaired by a mental illness or have an active substance abuse problem. Licensing boards ask about crimes (but not about tattoos). Direct patient boundaries are defined (or at least trying to be). But outside the office in settings that don't entail the purposeful inclusion of patients? Not many would criticize a doc for writing in academic journals. Novels? Blogs? A doctor who smokes but encourages his patients to quit? Take your lithium, but I've got to run to my hang gliding lesson now?

It's good to have a therapist who is a nice person, who is moral and ethical and kind and encouraging. It's good to have a psychiatrist who is well-educated about medications and up-to-date on treatment options (and kind and ethical and moral and encouraging and a nice person). Google your doc well if you want to be certain they don't have a blog or a strange hobby or affiliation, or crimes against humanity.

Why "transference" and not "the relationship?" Because that's how the question was posed to me. Sometimes my patients talk about the relationship, "transference" is not a word I tend to use in clinical practice, mostly because it's not a schema my patients bring to the setting.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

It's My Life, I'll Blog If I Want To

So while we were giving our talks on On-Line Communities and blogs at APA last week, a gentleman asked a question about "transference." I took the mic, I figured it was a question for me since I have the psychotherapy practice (in addition to being a Community Psychiatrist in clinics that serve the chronically and persistently mentally ill----I'm starting to get touchy about this).

So I talked a little about Transference to The Blog and how some of our readers seem to have their own ideas about us and who we are.

No No No No No! The gentleman wasn't talking about transference to the blog, he was talking about how my the existence of the blog effects my real live patient's transference to me! A totally different question. This has been an issue since day one, at least as an issue that other psychiatrists always raise to me. So far, I've been left to say that I'm not aware that any of my patients have found Shrink Rap. I wrote, way back when, about The Blogging Shrink

mostly in response to commenters who felt uncomfortable with the whole idea of a psychiatrist who blogs, maybe about their patients in a confidentiality-violating way, or maybe about the discomfort of knowing too much about what goes on inside their shrink's mind or life.

Since no one patient has told me they've read our blog, I talked instead about the responses I've gotten when patients have read my novel: Monday at The Charm. The truth is, none of the patients who've read it have been completely comfortable with it. One was obviously uncomfortable, the book is graphic, it has sexual (paraphilic, actually) content and the characters are a bit free with the expression of profanity. Clink, of course, was inspirational.

Whenever people asking me about my writing and my patients' reactions, inside I get a little queasy. Outside, I get a little defensive. It's as though I feel, or I hear, that by having a life other than the quintessential silent shrink life, I'm doing something wrong. You're not supposed to be out there, a literal open book for your patients to read. The old psychoanalysts went to great lengths to remain 'blank slates.' No family pictures in their offices, some didn't wear wedding rings, there were rules about who would leave if the arrived at the same party.

So I'm a writer. I don't volunteer this, my novel isn't displayed in my waiting room. I don't hide or deny it either, and if I have something I want to say, sometimes I say it rather publicly. I don't know how it effects my patients, and I don't know what I can do about this anymore than I could control if a patient found out something about my personal life. "How do you feel about this," is the best I could come up with.

And I'm not leaving a fun party if a patient shows up, but I might drink a little less and skip the tabletop dancing.

Before I go, the same gentleman asked about the gender of our readers: so please do take the sidebar poll.

Wednesday, May 07, 2008

How To Say Goodbye

In a few weeks I will be less of a ClinkShrink than I currently am. I'll still be a ClinkShrink, I'll just be doing it in fewer prisons. It feels odd to schedule my patients for followup knowing that I will no longer be there for their followup appointment. I am faced with the question of how to say goodbye to my patients, some of whom I've treated over multiple incarcerations in the last fifteen years.

Patients come in and out of my life fairly quickly. With a caseload of at least 150 patients or so, there's no way I can specifically remember each one. Often they disappear without warning, released to parole or transferred to other facilities. Sometimes I read about them in the newspapers later, either arrested or killed. That bothers me. I used to think that inmates didn't get attached to prison doctors because they move quickly through the system and see someone new at each pretrial facility. Generally though once they get into the sentenced side of the system, the prison side, this settles down and you have a chance to develop some longterm relationships. And the longer you work in the system the more inmates you get to know. Dinah thinks that when you're 'only' doing med checks the therapeutic relationship isn't important, but I can tell you it is. I'm going to miss (not all, but many) of these guys. If it matters to me, I'd be willing to bet it's going to matter to (not all, but many) of my patients.

The patients it will matter to are the ones who ask for me by name when they get arrested, the ones who insist on getting on the phone to say 'hi' when the nurse pages me for medication orders, the ones who honk and wave when they drive by me on the street, or run up to me in the recreation yard to tell me how they're doing. These are the patients who prove to me that kindness and a good rapport counts, even when you're 'only' doing med checks.

So I've been saying goodbye this week, not without a fair amount of guilt. Eventually I will be replaced but not right away, not for the full amount of time, and likely by someone with little or no correctional experience. I have sympathetic anxiety pains for the new clinician who has no clue what he's walking into, as well as for the inmate who sees the new face and has to start all over again.

But starting over is what the correctional experience is all about, for patients and sometimes also for physicians.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

You're Supposed to Get Better

In the comment section of my last post, Let Me Tell You About Myself, an anonymous commenter asked the following great question:

If one is comfortable with their therapist and feels the therapist seems to know what they are doing, how much lack of improvement should one tolerate before deciding it's time for a change? I know it's impossible to talk about an exact time frame given different diagnoses and personalities and treatment progress, etc etc, but is there any indication?And if so, what should one do? Bring it up with one's therapist and see what happens, switch therapists, get a second opinion? ...I was in a situation where I made no progress after 40 sessions and 3 drugs, had no experience with other therapists, and didn't think the therapy was going anywhere, but my therapist seemed competent.

Wow, where do I begin? Our questioner uses the term "therapist", and I'm going to substitute "psychiatrist" while I think about this because I'm simply not qualified to answer this from the point of view of another mental health professional. For the sake of this particular question, the fact that I prescribe medications makes, I believe, a huge difference in both who seeks my services and how I view outcome. Oh, and if no one minds, I want to talk about this in a vacuum, free from the discussion of insurance, reimbursement, "medical necessity", and who deserves care.

People come to psychiatric treatment for a variety of reasons, but most commonly because they are having a constellation of symptoms which someone (the patient, a family member, their primary care physician) has identified as being indicative of a mental illness. In plain English: people come to see me because they're feeling badly or acting weirdly. The patient comes with, for example, a complaint of sadness, changes in sleep and/or appetite, hopelessness, decreased energy, thoughts of death or suicide, decreased interest and activity.

A second reason people seek treatment is because they have experienced an overwhelming stress and they feel they are not coping with it well: the stress has resulted in either subjective distress, an inability to function normally, or the stress has precipitated a full-blown psychiatric disorder (back to where we started). For the sake of discussion, we can lump these first two groups of people together as patients with specific symptoms they want resolved.

A third common reason for seeking psychiatric treatment is that the patient is unhappy with the course his life has taken and feels he has maladaptive patterns of behaving and/or interacting which interfere with his ability to love or to work to his full potential. Sometimes people in this situation have personality disorders. Generally, people do not seek psychiatric treatment if they are having normal reactions to bad events or if they have no symptoms and believe they didn't get their last promotion because of bad luck or something completely external to them.

A second reason people seek treatment is because they have experienced an overwhelming stress and they feel they are not coping with it well: the stress has resulted in either subjective distress, an inability to function normally, or the stress has precipitated a full-blown psychiatric disorder (back to where we started). For the sake of discussion, we can lump these first two groups of people together as patients with specific symptoms they want resolved.

A third common reason for seeking psychiatric treatment is that the patient is unhappy with the course his life has taken and feels he has maladaptive patterns of behaving and/or interacting which interfere with his ability to love or to work to his full potential. Sometimes people in this situation have personality disorders. Generally, people do not seek psychiatric treatment if they are having normal reactions to bad events or if they have no symptoms and believe they didn't get their last promotion because of bad luck or something completely external to them.

Okay, so Patient Number One, with an acute onset of psychiatric disorder, wants his symptoms relieved. Often, medications are prescribed. Psychotherapy focuses on education about illness and support. People in a state of distress often feel an intense and powerful need to understand Why this has happened and want to talk about the precipitants of the episode, or if there are none obvious, their theories as to what may have gone wrong.

There is often a huge sense of relief simply in the telling of the story and the hopefulness of finding help. If the medications work, the patient often wants to end therapy or to come less often. People who are by nature a bit anxious often feel that regular therapy sessions keep them grounded and prevents recurrence. I don't know that they're right ( studies on Maintenance Psychotherapy, anyone?), however in those with repeated episodes of illness, if they are seen frequently it is easier to catch an episode and intervene early, and the patients who want to continue coming between episodes feel greatly comforted by psychotherapy for reasons that are sometimes difficult to articulate. One patient described therapy as a "safety net", and that's about as good as I've been able to get.

There is often a huge sense of relief simply in the telling of the story and the hopefulness of finding help. If the medications work, the patient often wants to end therapy or to come less often. People who are by nature a bit anxious often feel that regular therapy sessions keep them grounded and prevents recurrence. I don't know that they're right ( studies on Maintenance Psychotherapy, anyone?), however in those with repeated episodes of illness, if they are seen frequently it is easier to catch an episode and intervene early, and the patients who want to continue coming between episodes feel greatly comforted by psychotherapy for reasons that are sometimes difficult to articulate. One patient described therapy as a "safety net", and that's about as good as I've been able to get.

Let's move on to Patient Number Two: the person who is stuck in a bad place and thinks they should be getting more out of life. Sometimes people come to see me with a very specific concern: "I want to work on X" -- oh gosh, maybe feelings about a bad childhood, distress about a romantic relationship gone or going bad. These patients often talk for a few sessions, feel helped, and finish therapy quickly.

What about the patient with a personality disorder who repeatedly foils themselves or views life in a self-defeating way? These patients typically find me because they have a co-existing Axis I disorder -- meaning depression or anxiety or bipolar disorder, as in the last paragraph. But when their symptoms resolve with medications, their problems don't. These patients often continue with psychotherapy for a long time, and the therapy itself (and the therapist!) grow to have meaning above and beyond the issue of Fix the Problem, Doc. The end point becomes foggier, the treatment is more of a process, the goals may be clearly defined, but perhaps unattainable. And the treatment may start with the idea that progress will be slow and even painful. The relationship with the therapist may itself become a focus of attention, and this all gets muddled with what is going on with the illness and the meds and things are often just not so clear. Sometimes, it's not all that obvious exactly what is being worked on in psychotherapy and then, for lack of something that better describes what we do, therapy is deemed a "holding environment." I hate that term, and I like to know we're moving towards something, but that's just not always the case.

What about the patient with a personality disorder who repeatedly foils themselves or views life in a self-defeating way? These patients typically find me because they have a co-existing Axis I disorder -- meaning depression or anxiety or bipolar disorder, as in the last paragraph. But when their symptoms resolve with medications, their problems don't. These patients often continue with psychotherapy for a long time, and the therapy itself (and the therapist!) grow to have meaning above and beyond the issue of Fix the Problem, Doc. The end point becomes foggier, the treatment is more of a process, the goals may be clearly defined, but perhaps unattainable. And the treatment may start with the idea that progress will be slow and even painful. The relationship with the therapist may itself become a focus of attention, and this all gets muddled with what is going on with the illness and the meds and things are often just not so clear. Sometimes, it's not all that obvious exactly what is being worked on in psychotherapy and then, for lack of something that better describes what we do, therapy is deemed a "holding environment." I hate that term, and I like to know we're moving towards something, but that's just not always the case.

So How Long?

For someone seeing a psychiatrist with a psychiatric disorder, medications often provide relief. Medications take different amounts of time, not only to work, but to even tell if they are working. Typically, we say that antidepressants (just to use an example) take 3 to 6 weeks to work and they have to be given at high enough doses. If there is no improvement at all in a month, most psychiatrists will raise the dose or switch the medication. If there is partial response (some of the symptoms either resolved or lessened) then another medication -- an augmenting agent -- may be added. Sometimes it takes trying a bunch of medicines in a bunch of combinations, before results are seen, and this can take a while. If I start talking about antimanic agents and antipsychotics, we'll all be here for a while. As long as the patient is symptomatic and suffering, I believe this should be an active and aggressive process. Sometimes nothing works and all that's to be had for all the efforts are a lot of side effects.

For someone seeing a psychiatrist for an issue of dissatisfaction with their life, then it makes sense to stop and evaluate every few months. Are things getting better? Is there another way to go at the problem or something more or different that can be done? If the answer is repeatedly No Change at All, then it's reasonable to get another opinion or try something completely different.

Sometimes it's all very hard to quantify: even patients who don't get better, who continue to suffer or feel stuck, will identify therapy and the therapist as being helpful. Maybe they should get a second opinion, and often they don't want to.

I talk a lot. Please don't count my words. And don't forget to tell us who you are on our sidebar.

Friday, June 08, 2007

My Three Shrinks Podcast 23: Loons, Lefse, and the Flea

Just in case you need something to read while you listen: Chapter 8 is up on Double Billing.

Welcome back. Sorry for the delay in getting this out. I will be getting #24 out this Sunday, June 10. Be sure to check out this upcoming podcast as we will have a special guest joining us -- Dr. Phil.

June 3, 2007: #23 Loons, Lefse, and the Flea

Topics include:

- Doctor Anonymous to be guest on June 17 podcast.

- Clink brings back notepads with loons on them and cinnamon lefse from the midwest.

- Flea's medical blog affects his malpractice trial. This is a fascinating story, which is well-summarized and explained on Eric Turkewitz's legal blog. We're waiting for Flea's book to come out.

- Dinah talks about transference. Also see prior post on Transference to the Blog.

- Rules for Bloggers. In response to Flea's troubles, ClinicalCases suggests Five Rules for Blogging:

1-Write as if your boss and your patients are reading your blog every day

2-Comply with HIPAA

3-Do not blog anonymously. List your name and contact information

4-If your blog is work-related, it is probably better to let your employer know

5-Use a disclaimer

- We mention a survey of medical bloggers that was done last year. Anyone have a link?

- Movie Review: Away From Her. Clink thought this movie about a woman with dementia was very good.

- Oh, remember... check out next week's podcast, when Dr. Phil will be joining us for a brief interview.

| Find show notes with links at: http://mythreeshrinks.com/. The address to send us your Q&A's is there, as well. This podcast is available on iTunes (feel free to post a review) or as an RSS feed. You can also listen to or download the .mp3 or the MPEG-4 file from mythreeshrinks.com. Thank you for listening. |

Monday, June 04, 2007

Boundaries! Boundaries! Boundaries!

So the psychiatrist is talking to her own psychiatrist and he tells her he saw another psychiatrist in the hallway and this third psychiatrist, in the hallway, gave him a quick review of the literature on psychotherapy of sociopaths, and wouldn't you know it, it seems that psychotherapy validates, rather than cures, sociopaths, and it increases, rather than decreases their criminal recidivism rate. The first psychiatrist, who in this particular setting is the patient, becomes upset. It seems that her own psychiatrist believes that her years of work with a criminal patient have been a waste-- she hasn't helped the patient, rather she's harmed him and also society as a whole by increasing his comfort with his unconscionable violent behavior. And I'm thinking: Well that's not a very therapeutic thing for the psychiatrist to say to his patient!

Soon after, the psychiatrist and her psychiatrist are at a dinner party, with lots of other psychiatrists. What are they doing sitting together at a dinner party? If it's a professional thing, shouldn't they at least sit at separate ends of the long table? Another psychiatrist begins to discuss the negative findings of psychotherapy with criminals, and the first psychiatrist (now a dinner party guest and not a patient in this setting) gets angry with her own psychiatrist-- he set this up, he wants to convince her that she's wrong to continue her work with the sociopathic patient! And then to add to the mayhem, her psychiatrist tells the entire table the identity of his patient's famous criminal patient.

Soon after, the psychiatrist and her psychiatrist are at a dinner party, with lots of other psychiatrists. What are they doing sitting together at a dinner party? If it's a professional thing, shouldn't they at least sit at separate ends of the long table? Another psychiatrist begins to discuss the negative findings of psychotherapy with criminals, and the first psychiatrist (now a dinner party guest and not a patient in this setting) gets angry with her own psychiatrist-- he set this up, he wants to convince her that she's wrong to continue her work with the sociopathic patient! And then to add to the mayhem, her psychiatrist tells the entire table the identity of his patient's famous criminal patient.

So the poor psychiatrist/patient has transference issues with her own psychiatrist: she wants his approval. Even though after years of sympathetic therapy, he declared himself a HIPAA-violating jerk by telling their colleagues the identity of her nefarious patient.

So the sociopath comes for his regular psychotherapy session. Life has been hard: his son has been psychiatrically hospitalized after a serious suicide attempt and the Lexapro just isn't working for the kid, and come to think of it, only weeks ago his favorite nephew died after he killed him.

The sociopath is warm and gentle with his psychiatrist today, commenting on how meaningful her work is because she spends her days helping people the way she's helped him. The psychiatrist, now a complete transference-to-her-own-shrink/countertransference-to-her-gangster-patient mess, is visibly angry and fires the sociopathic patient after 7 years of psychotherapy. The angry sociopath leaves declaring the psychiatrist to be immoral, and I believe he's right.

I've watched this therapy evolve, and yes, it started with ducks. The series started when mob boss Tony Soprano presented to Dr. Melfi in the throes of panic attacks. Something to do with migrating ducks in his pool. Really. They've been through a lot together-- he's stolen her car to have it repaired, offered to off her rapist, driven her to drink, declared his love and survived the rejection. One more episode, and this is how they end?

ClinkShrink asked that I tell you that she wasn't any of the three psychiatrists mentioned above. And the weird thing is that I never knew Clink was in The Sopranos.

The Boston Globe had a nice write up about Tony's prospects for redemption that appeared before this episode aired: Tony Is A Monster

Labels:

forensics,

psychotherapy,

transference,

TV

Saturday, May 13, 2006

The Angry Patient

[posted by dinah]

Maybe this should be titled The Angry Psychiatrist.

The patient has had a rough time of it, he's a widower who tragically lost his wife, his only child is a disappointment to him, his boss is demanding and unpleasable.

I would listen sympathetically, but the patient won't talk. He stares at the ceiling and says he doesn't know what he should talk about. I make suggestions; they are all wrong. He's already talked about those things, and why don't I remember? Or he doesn't want to talk about them, it won't help. I ask about something I hope will be benign-- weekend activities, how things are with a family member, even a TV show I know he likes, but anything that isn't charged, he's deemed a waste of therapy time. "What's important to talk about?" I ask, trying every angle I can think of. "You're the doctor," He replies. But it's not a matter-of-fact, or even a slightly annoyed, reply--it's a hostile, you're failing me, dig and he knows right where to aim.

When he does talk, it is to rail at me. I'm not helping him, the medications aren't helping him, the side effects suck. He logs my failures: the time I didn't call his meds in fast enough, the time he was certain he'd left a message I didn't return-- it doesn't matter that I tried and couldn't get through. If I make any reference to the future, one he insists won't come, he uses it as an opportunity to angrily tell me how I haven't been where he's been. He stares at my wedding ring and asks how I'd feel if my husband died, if my kid had the problem his kid has? He makes many assumptions that I've never suffered, and certainly, he announces, not the way he has.

The Angry Patient never misses an appointment, in fact, he arrives early, and he sometimes calls between sessions. He comes, he says, because he is hanging on to his last remnant of hope. He's never had a kind word for me, never even an ounce of tenderness to his tone. I've tried to suggest he see someone else (pleeeease...), for at least a consult. Empathy, I've said, is a necessary part of the psychotherapeutic process, and he feels I have none; perhaps he might find it with someone else? Even I'm giving up on him, he's quick to point out, and I'm not surprised-- I knew he'd see my referral as a rejection. He's not telling his story again, not starting over, and I'm as good as the rest of the quacks (he's test driven quite a few). Gee, thanks, I think.

The Angry Patient stares at the ceiling and I glance at the clock. I keep my tone gentle and even. I listen and I try not to say the wrong thing. I remind myself that he's still grieving, and I try to garner some sympathy for his disabling narcissism, his Cluster-B-ness which he wears like a coat of armor.

If the Angry Patient were just angry, that would be fine. Why does he have to be angry at me? Don't answer that; for the moment, I'm just striving for survival.

Maybe this should be titled The Angry Psychiatrist.

The patient has had a rough time of it, he's a widower who tragically lost his wife, his only child is a disappointment to him, his boss is demanding and unpleasable.

I would listen sympathetically, but the patient won't talk. He stares at the ceiling and says he doesn't know what he should talk about. I make suggestions; they are all wrong. He's already talked about those things, and why don't I remember? Or he doesn't want to talk about them, it won't help. I ask about something I hope will be benign-- weekend activities, how things are with a family member, even a TV show I know he likes, but anything that isn't charged, he's deemed a waste of therapy time. "What's important to talk about?" I ask, trying every angle I can think of. "You're the doctor," He replies. But it's not a matter-of-fact, or even a slightly annoyed, reply--it's a hostile, you're failing me, dig and he knows right where to aim.

When he does talk, it is to rail at me. I'm not helping him, the medications aren't helping him, the side effects suck. He logs my failures: the time I didn't call his meds in fast enough, the time he was certain he'd left a message I didn't return-- it doesn't matter that I tried and couldn't get through. If I make any reference to the future, one he insists won't come, he uses it as an opportunity to angrily tell me how I haven't been where he's been. He stares at my wedding ring and asks how I'd feel if my husband died, if my kid had the problem his kid has? He makes many assumptions that I've never suffered, and certainly, he announces, not the way he has.

The Angry Patient never misses an appointment, in fact, he arrives early, and he sometimes calls between sessions. He comes, he says, because he is hanging on to his last remnant of hope. He's never had a kind word for me, never even an ounce of tenderness to his tone. I've tried to suggest he see someone else (pleeeease...), for at least a consult. Empathy, I've said, is a necessary part of the psychotherapeutic process, and he feels I have none; perhaps he might find it with someone else? Even I'm giving up on him, he's quick to point out, and I'm not surprised-- I knew he'd see my referral as a rejection. He's not telling his story again, not starting over, and I'm as good as the rest of the quacks (he's test driven quite a few). Gee, thanks, I think.

The Angry Patient stares at the ceiling and I glance at the clock. I keep my tone gentle and even. I listen and I try not to say the wrong thing. I remind myself that he's still grieving, and I try to garner some sympathy for his disabling narcissism, his Cluster-B-ness which he wears like a coat of armor.

If the Angry Patient were just angry, that would be fine. Why does he have to be angry at me? Don't answer that; for the moment, I'm just striving for survival.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)