Dinah, ClinkShrink, & Roy produce Shrink Rap: a blog by Psychiatrists for Psychiatrists, interested bystanders are also welcome. A place to talk; no one has to listen.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

No One Likes Me

If you check out the today's posts over on KevinMD, you'll notice that Kevin picked up my post on the ethical dilemma of the college student and the internship application. You'll also notice that the post was tweeted 37 times, and that no one "likes" it on their Facebook page. The story on the Therapeutic Value of Touch got 56 "Likes" and the Art of Alzheimer's got 26 "Likes." My story is alone in it's unlikability.

And now that you mention it, our posts on Shrink Rap don't have many Likes and our fan page doesn't have very many fans/friends.

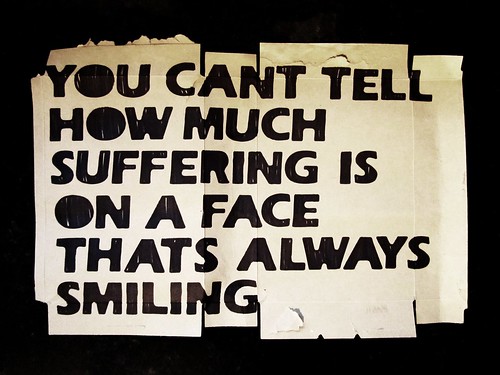

You know, I would take it personally, but when we first put the page out, one of our readers mentioned that if they "Liked" a psychiatry book, all their friends would see and would wonder why. Is it true? I don't think too hard about what other people "Like" but for the non-stop political stuff. But then again, I have a socially acceptable reason to "Like" a Shrink Rap book (--I think, my kids would probably say it's bragging to like your own book). So maybe people don't "Like" shrinky stuff because they don't want to worry about the message it sends and the questions this might open, either aloud or in the viewers head. Or maybe I just write boring stuff and this is my way of defending my ego against demoralization.

Just in case you're wondering, 262 people "Liked" my Analysis of the Angry Birds addiction when it was posted on KevinMD. Maybe that was a safer "Like." But who's counting?

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

'Tis the Season

Saturday, November 26, 2011

Please Don't Tell

Earlier, we were talking about an ethical dilemma in The Very Badly Behaved Health Care Practitioner-- What should a therapist do if he's treating another therapist who confesses he's been having an affair with a patient? Should the treating therapist report his patient to their respective licensing board? Of course, the comments are the most interesting part of that post.

Earlier, we were talking about an ethical dilemma in The Very Badly Behaved Health Care Practitioner-- What should a therapist do if he's treating another therapist who confesses he's been having an affair with a patient? Should the treating therapist report his patient to their respective licensing board? Of course, the comments are the most interesting part of that post. It got me thinking about two things: Doctor-Patient Confidentiality and What is a Patient?

From the Encyclopedia of Everyday Law:

The Oath of Hippocrates, traditionally sworn to by newly licensed physicians, includes the promise that "Whatever, in connection with my professional service, or not in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge, as reckoning that all such should be kept secret." The laws of Hippocrates further provide, "Those things which are sacred, are to be imparted only to sacred persons; and it is not lawful to impart them to the profane until they have been initiated into the mysteries of the science."

Doctor-patient confidentiality stems from the special relationship created when a prospective patient seeks the advice, care, and/or treatment of a physician. It is based upon the general principle that individuals seeking medical help or advice should not be hindered or inhibited by fear that their medical concerns or conditions will be disclosed to others. Patients entrust personal knowledge of themselves to their physicians, which creates an uneven relationship in that the vulnerability is one-sided. There is generally an expectation that physicians will hold that special knowledge in confidence and use it exclusively for the benefit of the patient.

Most psychiatrists I know (at least in Maryland) do not violate their patients' confidentiality unless 1) there is an issue of child abuse and this is because state law mandates it be reported, and 2) there is an imminent risk of danger to self or others. There may be reasons other physicians break confidentiality, for example the mandated reporting of contagious diseases or driving issues with epilepsy, but these do not generally happen in psychiatry. The thinking behind doctor-patient privilege is that no one would trust a physician if they worried their problems would be repeated. When I am not sure what to do, I will ask a trusted colleague, but there are clearly times when what is in a patient's best interest is not what's in society's best interest (such as prescribing an expensive medication or ordering an expensive test or revealing information learned in treatment) and I generally feel that my job is to keep my patient's best interest in front of me. It's hard to be everyone's agent.

For the most part, I don't endorse laws that mandate the reporting of past child abuse against the wishes of the patient (--not that anyone has ever asked me, but hey, it's my blog so you get my opinion) --at least not by psychiatrists as an after-the-fact event. In an Emergency Room with an injured child victim it's a different story and it's hard to imagine that it would ever be in the best interest of the patient to send them home to a violent setting. For psychiatry, I believe that such laws prevent people with problematic behaviors from getting help, and they prevent victims of abuse from having therapy if they do not want the scrutiny of the legal system or the turmoil that may bring if family members were involved. If a patient reports an active urge or plan to commit a violent crime, taking action is generally in that patient's best interest as well as society's and violating confidentiality may be the clear right choice.

In the vignette given in the Badly Behaved Behavior Health Care Practitioner, the situation asked whether a therapist should report a patient who is also a therapist who is having a sexual relationship with an adult patient. There is no "law" about reporting such behaviors (at least not in our state), though some Licensing Boards make statements that professionals are required to report colleagues who are impaired or incompetent. Some of our commenters wrote in to say that the therapist should be reported-- that patient safety should come first. My thought was that when a patient walks in the door for treatment, she is a patient and not a colleague and such licensing mandates do not pertain the way they would if the therapist in the next office knew illicit sexual activity was going on. It seems to me that the spirit of such mandates is to get the licensee help, something she is already doing by seeking care, and that these mandates were probably not made in the spirit of trumping confidentiality with patients, but I could be wrong. Reporting the therapist might help prevent future harm to patients, but in the big picture, it means that badly behaving psychotherapists can never get help in a confidential setting.

I suppose one way to get help for a misbehaving therapist to get help would be to seek care from a therapist in another specialty-- there is nothing in the Licensing Board mandates that suggests a licensee needs to report an incompetent member of another specialty or profession, so a social worker who is having an affair with a patient could perhaps seek treatment from a psychologist or a psychiatrist? And the other thing I wondered about-- does reporting the therapist necessarily help the current victimized patient? An adult patient, after all, is free to report her abusive therapist. If she chooses not to, perhaps there is a reason-- perhaps it would blow apart her marriage, or perhaps the inquiry that comes with such events would leave the victim feeling even more victimized. These aren't easy scenarios-- one can imagine all types of configurations-- the victim could deny the abuse/affair happened, the victim could be thrilled to hear that a confession occurred which will help with the prosecution, or the victim could feel not at all like a victim, but like someone who chose to have a consensual relationship and does not want the attention of the therapist's disciplinary proceedings.

These are really difficult situations. I'm not sure what the rules are for psychologists or social workers, but for physicians the default requirement is for confidentiality and there needs to be a really good reason to violate it, and revealing a patient's secrets may leave the psychiatrist open to his own scrutiny, disciplinary action, and lawsuits. We treat people even when they have behaviors or beliefs that are deplorable to us. I hesitated, however, to write this, because I can think of scenarios where confidentiality in the doctor-patient relationship might warrant a breech, and I'm happy I've never been faced with one of these situations.

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Guest Blogger Dr. Ron Pies on Internet Anonymity

Internet Anonymity: Is it Ever Justified?

Consider Meagan’s dilemma. She is a 30-year-old, separated store clerk who is now living in a shelter for battered women. Meagan was severely abused by her husband, and now takes care to conceal her whereabouts, lest he try to find her. Using the internet connection at her public library, Meagan finds a website that deals with issues of battering, including help for those women (or men) who want to obtain a restraining order against the abusing spouse. Meagan would like to participate in the online discussion, but is afraid to use her full name. She suspects that her husband “tracks” websites like this, and that he might retaliate violently if he sees her name. She chooses to use a pseudonym and posts a letter on the website.

Is Meagan justified in concealing her online identity? I would not hesitate in saying that she is. I would take the same position when someone faces reprisals from a totalitarian regime, such as protesters in Iran and Egypt; or in the case of a “whistleblower” who wants to expose a public danger online, without risking being fired.

But absent such compelling dangers to life, limb or livelihood, I am generally opposed to the use of pseudonyms or anonymous postings on the internet. Of course, there are exceptions beyond those I have noted, and each case must be considered individually. But as a rule, I believe that the burden of justification should be on the individual who chooses to conceal his or her identity, and that website monitors ought to be exceedingly selective in accepting unsigned or pseudonymous letters.

I am speaking, of course, from the perspective of a psychiatric physician who is used to posting my blogs with “full disclosure”—not only of my name, but also of my potential conflicts of interest. (Having retired recently from clinical practice, and having no financial connections to pharmaceutical companies, my only “conflicts” these days are the ones a psychoanalyst would explore—but for those who want to delve, my disclosure statement is viewable on the Psychiatric Times website, at:

The issue of personal disclosure bears on one reason I am opposed to anonymous blogs and postings: the general public has no way of determining what, if any, concealed agenda or conflicts of interest the anonymous blogger or commentator may have. I find this issue especially pertinent when the unidentified person launches a personal attack against someone who is identified by name, profession, etc. As a psychiatrist who blogs fairly often on both the Psychcentral and Psychiatric Times websites, it is especially upsetting when an alleged “health care professional” posts a highly critical, anonymous comment, in response to an article or essay I have written. In my view—barring some of the exceptional circumstances I outlined earlier—a physician, nurse, psychologist, social worker or other health care professional has no business concealing his or her identity when voicing an opinion on a professionally-related topic, especially when taking aim at a colleague. I consider such “drive-by flaming” both professionally irresponsible and ethically unjustifiable. It is also downright rude and inconsiderate—what my dad would have called “a cheap shot”!

So why do so many health professionals post anonymously, or sign their emails as “MiffedDoc” or “Irateinternist”? I think that, in many cases, it is a simple wish to avoid embarrassment or discovery, either by patients or by colleagues. And, in my view, that excuse simply doesn’t cut it. My understanding of professional ethics is that you should be willing to stand behind anything you say in a professional context, and that your audience has a right to know who you are and who may be standing behind you—the American Medical Association? The Scientologists? The government of Iraq? Readers Digest?

Sure, there may be exceptions to this rule. I can imagine a health care professional who is revealing an extremely sensitive personal issue—let’s say, a problem with substance abuse—who does not want to disclose his or her name. Yet he or she believes that the message has important public health implications. So, Dr. X may be posting a message saying, “As a physician who has had a problem with alcohol abuse, I would urge all my colleagues to report obvious substance abuse problems among their colleagues to the appropriate authorities...” OK—anonymity in this context is understandable, Doc.

By the way, I also believe we have an ethical responsibility to avoid attacking another person’s character, engaging in gratuitous insults, casting aspersions, or just plain being rude! (For more on “internet ethics”, please see my essay originally posted on the Psychiatric Times website, and also viewable at: http://www.jeffpearlman.com/todays-cnn-com-column-3/). A good rule of thumb, which I try (not always successfully) to live by: if you wouldn’t be comfortable saying something to a person face-to-face, think twice about saying it in an anonymous internet message. (You might just run into that individual at a conference!).

Only when self-disclosure poses a great personal risk are we justified in hiding behind anonymity. In short, all of us have a responsibility not only to tell the truth, but to tell the truth about who we are.

****************

Ronald Pies MD is Professor of Psychiatry and Lecturer on Bioethics & Humanities at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY; and Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston. The views expressed here are solely his own.

Note: Dr. Pies does not reply to unsigned, anonymous, or pseudonymous messages, except when the justification for anonymity is clear.

Monday, November 21, 2011

The Stability of Psychiatric Diagnoses

We've talked a lot about diagnoses here on Shrink Rap. We've talked about how diagnoses are made, how valid they might be, how as labels they can be stigmatizing or damning in a person's life. We've talked about how they are used to guide treatment and how they are demanded to obtain reimbursement for care. What we haven't talked about is how they hang out over time.

When I see a patient for the first time, we meet for 2 hours, I take a full history, family members may come in, and subsequent to the appointment, I may talk with a past psychiatrist, a current primary care doc, and I may request old records that I will review. I take the information I have and I form a diagnosis. Is it the right diagnosis? Oh, who knows. I don't sit there with the DSM and read off a check list and some of it is art. The DSM diagnoses aren't science, they were voted on by a committee. I come close. Like what is the exact divide between Major Depression, recurrent, mild versus Major Depression, recurrent, moderate ? To the extent that it guides treatment, I care about getting it right, but sometimes the honest answer is I Don't Know. Or the patient comes to me after they have gotten well--- they are not currently having symptoms, but they are on medications which they say help, and they report that before they were on medications, they had symptoms consistent with Diagnosis X. If they are medications that are usually used to treat Diagnosis X, if they had symptoms consistent with Diagnosis X, I believe them and diagnosis X.

So here's how treatment goes. Usually the patient has symptoms and the majority of the time the symptoms are consistent with a specific diagnosis and everyone agrees. Let's say the diagnosis is recurrent major depression, moderate in intensity, coded 296.32. I start the patient on medications for this condition and they come for therapy. A few weeks go by, and the patients symptoms get better, but they still have issues going on in their life. Stressful things that they are dealing with, or troubling relationships, or life just not going the way they'd like, so they still come for therapy. And each visit, a bill is generated and the bill needs a diagnosis, so the diagnosis remains, because this is what is being treated and this is what the patient is getting medications for, and so it's 296.32, even if the patient's symptoms are at bay, or even if the patient comes in saying that they are anxious today, or even if the patient spends the entire session talking about the fight they had with their sister and never mentions a word about their mood or symptom complex. The diagnosis is usually a stable thing for the paperwork issues that call for it. I mentioned statements for insurers, but in clinics, it needs to be on treatment plans, and in EMRs, and any form that goes to an agency which has regulations, including Day Programs, Psychosocial Rehab programs, Care provider organizations, etc. No diagnosis, no services. And some services are only accessible to the patient with specific diagnoses that indicate a severe and persistent psychiatric illness. I would say that for a patient who has had numerous psychiatric hospitalizations, is unable to work, gets benefits from the government because they are disabled by mental illness, and requires medication to remain well, it seems reasonable to agree that a major psychiatric disorder exists, even if on a given day, the patient says he is not having any symptoms of the illness and is feeling well. It has to be this way, or no therapy would ever be done: every session would be a diagnostic evaluation with check lists of symptoms. Now I'm not saying that diagnoses never change...they do...people get manic and we realize that their unipolar depression is really bipolar depression, or with time we realize that there is more than one diagnosis, or that a preliminary diagnosis was simply wrong, or that alcohol or drugs were a bigger contributor to the symptom complex than we realized at first.

But when our theoretical patient, the one with major depression, moderate, who had a long hard course with it, notes that a long time has gone by with no symptoms of the illness (on medications and with therapy) and he asks, "So do I still have depression?" it does make for an interesting session.

What do you think?

Thursday, November 17, 2011

The Very Badly Behaved Health Care Practitioner

I've been asked several 'ethical dilemmas' in the past few weeks. I'm putting them up on Shrink Rap, but please don't get hung up on the details. These aren't my patients, but the details of the stories are being distorted to disguise those involved. The question, in both cases, boils down to: Should the mental health professional report the patient to his professional board?

In the first case, a psychiatrist is treating a nurse who is behaving badly. The nurse is stealing controlled substances from the hospital and giving them to friends who 'need' them. She doesn't intend to stop, and her contact with the psychiatrist was only for an appointment or two before she ended treatment. Should the psychiatrist contact the state's nursing board? Is he even allowed to?

In the second case, a psychotherapist sees a patient who is also a psychotherapist (I will call the patient here the patient/therapist). The patient tells the therapist he having a sexual relationship with one of his own patients (the patient/victim). This is clearly unethical, but the patient/victim is an adult and the relationship is "consensual" in that it is not forced or violent. There is no question that if a licensing board knew of this, the patient/therapist would lose his license. Should the treating therapist report his patient for unethical behavior? Ah, he asked a colleague on the Board and was told that he must report this, and if he doesn't, his own license could now be at risk. If he now reports it, as instructed, can the patient/therapist turn around and sue him for breaching his confidentiality? After all, he was seeking help with his problem, he believed it was protected information, and now he will be sanctioned out of a livelihood. Does it matter if the therapist is a physician (for example, a psychiatrist) as opposed to a psychologist or social worker or nurse practitioner? I realize that all mental health professionals have confidentiality standards, but are the confidentiality laws that apply to physicians/clergy/attorneys the same as they are for other mental health professionals?

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

Technology and The Shrink-- Hello, Siri.

Technology seems to be the theme of the moment here on Shrink Rap. We're all playing with new toys and trying to figure out what makes them fun and what makes them useful to our work.

For this week's post on Shrink Rap News over on the Clinical Psychiatry News website, I have an article up on Siri and the Psychiatrist. Some information that might be useful to anyone who is thinking of incorporating this technology into their practice, and oh, a little tongue-in-cheek humor there with many thanks to Dr. Bob Roca at Sheppard Pratt and Dr. Paul Nestadt at Johns Hopkins who both allowed me to quote them during their more playful moments. There is also a techy post up on Shrink Rap Today over on our Psychology Today Website with links to some of our past technology posts.

Roy is trying to figure out how to use his iPad to interface with Electronic Medical Records and wrote about it last week for our Clinical Psychiatry News SR blog, see iPad: The New Black Bag. His last post on Shrink Rap was about Depression Apps, and he inspired me to add the Moody Me app to my own iPhone. I haven't tried it yet, but I'll let you know how it goes, but the colorful smiley faces were more than I could resist. Depression Apps will also be a topic in one of our upcoming podcasts.

Okay, so if you read my post on Siri and the psychiatrist, it will make me happy:

If you comment on it, it will make me really happy:

But be nice, I don't want to be sad:

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Depression Apps

In My Three Shrinks Podcast #63 (recorded last Sunday, to be out as soon as Clinkshrink completes it), we talked about reviewed iTunes apps helpful for screening for or tracking depression. I will provide a bit more focus on this topic here.

I recently wrote an article for Clinical Psychiatry News referring to the iPad as the new physician's "black bag." One of those tools might be a depression tracking app, to be used by patients or by providers responsible for treating patients. So, I went to the App Store (sorry Android users, I don't have one of those gizmos yet) and searched for the keyword "depression" and narrowed it down by filtering for apps which met the following criteria: Medical category; a rating of at least 3 stars; and at least 100 ratings.

Five apps came up:

3D brain

- 9600 ratings

- not a rating tool but a nice 3D map of the brain

- interactive features

- 800 ratings

- uses a Zung depression rating scale

DepressionCheck

- 700 ratings

- uses a 27-item validated screen for depression, bipolar, PTSD, and anxiety

- displays graph of scores over time

- ability to send to your doctor

- also has a physician dashboard for reviewing trend of scores for all your patients

Moody Me

- 600 ratings

- an emoticon-based mood diary

- displays a graph of your scores over time

Health through Breathing: Pranayama

If you have used any of these, please tell us about your experience. If you have others you like, let us know.

*Disclosure: I have consulted for and collaborate with M3, the makers of DepressionCheck.

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Guest Blogger Dr. Jesse Hellman on The Penn State Matter

The news media has published numerous pieces exploring various aspects of what happened at Penn State. The sports culture, the prestige of the program, the money it brought into the university, the parallels with the Catholic Church, and so on. What kept action from being taken by administrators after an employee allegedly witnessed a violent crime? What kept that employee from stopping a violent act? What kept him from taking further action later?

The media has looked at various aspects of these questions, but two aspects have received little attention: Is there a difference between the way men and women react to these events, and are there factors that actually inhibit men from taking action in these circumstances?

Here is a "thought experiment:" What would happen if the alleged crime were different-- if, for example, a man had walked in on someone violently raping a ten year old female child? Would he have reacted the same, observing but not interfering, reporting it up the line, but not taking subsequent action? What would have happened if one of the administrators who learned of this had been a woman? My thesis is that it would have been very different if it had been a little girl, and that women involved as administrators would have been far less likely to ascribe this to "horse play," look the other way, and remain passive after reporting it up the line to superiors.

A man coming across a heterosexual rape, whether of an adult or a child, would know immediately that this is a terrible crime and would have immediately stopped it. It would be clear that the police should be involved. I wonder whether the homosexual act, even with a child, arouses feelings in men that actually inhibit action, that make it easier to turn away and rationalize not taking action. It is something that is harder to confront, to even think about. To the psyche it is perhaps the most forbidden of crimes, worse than incest.

Again, the purpose of this post is to discuss the general principles, not the individual actions at Penn State, of this subject. What are the Psychological Factors that inhibit Action when Evil is

Encountered?

Labels:

politics,

psychodynamics,

sex offenders

The History of The Duck, etc....

Those of you who are regular Shrink Rap readers know we are rather attached to the image of the yellow rubber duck. It started with an article on Emotional Support Animals that was in the New York Times right after we started our blog, and we latched on to the imagine of airline passengers who brought ducks (one dressed in clothing) on to flights, and then Clink began her years-long hobby of animating ducks! And of course there was the lovely reader, DrivingMissMolly, who donated a flock of ducks to Heifer International in our behalf. The duck appears on our blog, it was the subject of heated debate and designated committee meetings when our book was in press (see They Nixed the Duck!) and it's on our logo in the print version of our column on Clinical Psychiatry New. We distribute candy ducks at all Shrink Rap public events.

Needless to say, I was quite pleased to see an article in this morning's New York Times Magazine on the history of rubber ducks. In "The Rubber Duck Knows No Frontiers,' Hilary Greenbaum and Dana Rubinstein write:

This yellow, doe-eyed icon — a preferred bathtub ornament of toddlers and royals alike — would have never existed were it not for Charles Goodyear. The Massachusetts inventor discovered the chemical process that renders rubber more malleable (and thus appropriate for toys) by, as legend has it, inadvertently dropping a mixture of rubber and sulfur into a potbelly stove. Goodyear, who died in 1860, never benefited from this discovery, but his vulcanization process revolutionized the rubber trade.

Greenbaum and Rubinstein go on to note:

Still, it was only when Ernie, of Bert and Ernie fame, took a bubble bath with a rubber duckie in 1969 that the toy became inescapable. According to Tim Carter, a senior producer at “Sesame Street,” the story goes like this: Someone gave a rubber duckie to a “Sesame Street” writer named Jeff Moss, who put it in his bathroom window. One night while taking a bath, Moss looked over and had an epiphany. And “Rubber Duckie” subsequently reached No. 16 on the Billboard chart. “It wasn’t until ‘Sesame Street,’ ” says Charlotte Lee, a Seattle-based engineering professor who holds the Guinness World Record for the largest collection of rubber duckies, “that a rubber duck became a special thing.”

For those who would like a psychodynamic interpretation of Ernie's relationship with his duckie, Shrink Rap provides one Here.

--------------------

In other Shrink Rap events:

- Clink has an article up on Shrink Rap News on how social media does a lousy job of representing Forensic Psychiatry. Please do read What Follows Is Fiction: What Orson Welles Can Teach Us About Social Media.

- We enjoyed our book signing at Baltimore's Ivy Book Shop on Friday evening and met some great people. We posted a photo of ourselves with author Gilbert Sandler-- he says he needs all the help he get. He's a charming man! Do visit our Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/shrinkrapbook to see event photos, and do click the link to "follow" us on Facebook for the latest Shrink Rap updates.

- We are podcasting later today, we should have new episodes of My Three Shrinks up in the coming weeks.

- Jesse tells me he's planning to submit a guest post about factors that keep people from reporting heinous crimes, so do check back later today. The events at Penn State seem to have everyone stirred up.

Wednesday, November 09, 2011

All About Me!

Psychotherapy is, by it's nature, a narcissistic endeavor. That's not to say that the patient is a narcissist, but the journey itself is meant to focus on patient's interior life, and it's not always about the greater good. In my last post, several commenters said they feel uncomfortable talking about themselves or worry that their therapist will mistakenly think they are narcissistic because they that talk about themselves in therapy.

It's not at all unusual for people to express some discomfort about talking about themselves in therapy, or to comment, "all I do in here is complain," or "You must get tired of hearing people complain/talk about their problems, etc...."

I won't talk for other psychotherapists because I only know how I feel. It seems to me that the mandate of therapy is for the patient to talk about the things they have been thinking about. The truth is that most people think about themselves and issues of the world are interpreted by individuals as they impact them. Some people have lives that are very much focused around their immediate circle of events, the pain of their emotions, the distress of interactions with family, neighbors, friends, and co-workers. Others may spend time discussing how the people around them are behaving in unproductive ways, and some people focus on their concerns about broader political issues that are important to them. Most people don't come to spend their entire psychotherapy sessions discussing world events, problems in developing nations, the European economy, climactic issues in other parts of the country, or other world events unless these things directly impact them, or they are things they are spending a lot of time thinking about.

I like hearing about people's problems. I may empathize or sympathize or say things I hope will provide some sense of support, or perhaps offe an interpretation that will give the issue a broader meaning in the context of the patient's life, but I don't generally feel burdened by other people's problem. I am too busy feeling burdened by my own problems, and for the sake of my job, I get the luxury of being able to turn off my own problems and focus on someone else's internal world for 50 minutes out of the hour. I like this and I get paid for it.

Do I ever think a patient is narcissistic? Well sure, if they tell story after story where they seem completely unable to see that another person might have a different point of view, or repeatedly recount events where they've behaved with complete disregard for the feelings of others or respect for the law. For most of the people, most of the time, I think they're just people who come to therapy and they talk about themselves because that's what therapy is about. Am I bored? No. Do I ever wish a session would end and I could finish the day and go home and change out of work clothes and chill out and think about my own stuff? Yes, but that doesn't mean I find my patients boring, or that I don't care about them, or that I don't like listening , or that I don't like them. I think it means that sometimes I'm human.

Mostly, I listen and try to be helpful. I don't spend a lot of time judging. (I can't say never because I'm a human being and human beings sometimes judge each other and you may think a psychiatrist should never do that but do write me when you've examined the content's of someone's heart and you've found the perfect non-judgmental person; I would like to have coffee with them.)

If you're worried that you're psychiatrist thinks you're too self-involved because you talk about yourself in therapy, you might want to find something else to worry about. ;- ) (Roy will be back soon to translate my emoticons).

And just a quick fyi: the definition of narcissism per wikipedia:

Narcissism is a term with a wide range of meanings, depending on whether it is used to describe a central concept of psychoanalytic theory, a mental illness, a social or cultural problem, or simply a personality trait. Except in the sense of primary narcissism or healthy self-love, "narcissism" usually is used to describe some kind of problem in a person or group's relationships with self and others. In everyday speech, "narcissism" often means inflated self-importance, egotism, vanity, conceit, or simple selfishness. Applied to a social group, it is sometimes used to denote elitism or an indifference to the plight of others. In psychology, the term is used to describe both normal self-love and unhealthy self-absorption due to a disturbance in the sense of self.

Monday, November 07, 2011

Is it Ever Okay to Lie?

We've been having a great discussion over on the post Tell Me.... An Ethical Dilemma. The post talks about a young man who wants to know if he can check "no" to a question about whether he has a psychiatric disorder if his illness is not relevant to the situation. The comments have been fascinating -- do read them-- and very thought-provoking.

One reader asked, " If a patient asked if they were boring you, and they were, would you say yes?"

This is a great question, and of course the right thing to do is to explore with the patient what meaning the concern has to him. But is that all? I'm not very good at doing the old psychoanalyst thing of deflecting all questions, and mostly I do answer questions when they are asked of me. This can present a really sticky situation because one can not think of any clinical scenario in which it would be therapeutic to have a therapist tell a patient, 'Yes, you're boring, OMG are you boring,' or 'No, in fact, I don't like you.' And not answering could be viewed as negative response by the patient --if you liked me, you'd tell me, so clearly you don't like me. So if the exploration of the question doesn't take care of the issue, and the patient continues to ask, what's a shrink to do?

I'm not in favor of lying to patients, therapy is about having an honest relationship, but our readers have given some great examples. If a gunman asks for your money, is it okay to lie and say you have none? Is it okay to lie about whether you've been the victim of sexual abuse on a job application (one reader saw this!). Just because someone asks, do you need to answer truthfully? Of course, you can be truthful and say you don't plan to answer that question, but so many times, the assumption is that the answer must be Yes because if not, you'd have nothing to hide.

Psychiatrists don't owe it to their patients to be totally transparent. Shrinks have the right to their privacy, and professional boundaries dictate that it's wrong to share your problems with your patients (even if they ask).

That being said, it still can feel very uncomfortable on the shrink side of a couch when a boring patient asks if they are boring. What would you say?

Saturday, November 05, 2011

Trading Stacks for Page Views

Whoa, I think this news marked a turning point for medical educators:

Here's an article on ZDNet.com about the Johns Hopkins medical library shutting down for good. No more bricks-and-mortar, wandering the stacks, paging through paper medical research. I spent a fair amount of time in real, physical medical libraries during my training. I have to say, being able to log in from the comfort of the living room couch and download any PDF I need is the way to go. Nevertheless, I couldn't help but feel a twinge of nostalgia.

**********************

And now for something completely different. I thought you might enjoy our new animated mascot!

Come Meet the Shrink Rappers at the Ivy Book Shop on Friday, November 11

JHU Press Night at the Ivy Book Shop on November 11

Meet some of the Press’s local authors and get a jump on holiday shopping at the Ivy Book Shop’s JHU Press Night on November 11, from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. The event at the popular independent book store in north Baltimore is free and open to the public, and refreshments will be served.

Meet some of the Press’s local authors and get a jump on holiday shopping at the Ivy Book Shop’s JHU Press Night on November 11, from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. The event at the popular independent book store in north Baltimore is free and open to the public, and refreshments will be served.

More than a dozen JHU Press authors will be on hand to meet guests and sign books, including: Gil Sandler (Home Front Baltimore); Cindy Kelly (Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore); Mike Gesker (The Orioles Encyclopedia); Charley Mitchell (Maryland Voices of the Civil War); Michael Olesker(The Colts’ Baltimore); Fraser Smith (Here Lies Jim Crow); Bryan MacKay (Baltimore Trails); Ed Papenfuse (Maryland State Archives Atlas of Historic Maps of Maryland); Frank Mondimore and Patrick Kelly (Borderline Personality Disorder); Sara and Jeff Palmer (When Your Spouse Has a Stroke); Dinah Miller, Annette Hanson, and Steve Daviss (Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work).

More than a dozen JHU Press authors will be on hand to meet guests and sign books, including: Gil Sandler (Home Front Baltimore); Cindy Kelly (Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore); Mike Gesker (The Orioles Encyclopedia); Charley Mitchell (Maryland Voices of the Civil War); Michael Olesker(The Colts’ Baltimore); Fraser Smith (Here Lies Jim Crow); Bryan MacKay (Baltimore Trails); Ed Papenfuse (Maryland State Archives Atlas of Historic Maps of Maryland); Frank Mondimore and Patrick Kelly (Borderline Personality Disorder); Sara and Jeff Palmer (When Your Spouse Has a Stroke); Dinah Miller, Annette Hanson, and Steve Daviss (Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work).

The Ivy Book Shop is located at 6080 Falls Road, in the Lake Falls Village shopping center at Falls Road and Lake Avenue in Baltimore.

For more information, call The Ivy Book Shop at 410-377-2966.

Meet some of the Press’s local authors and get a jump on holiday shopping at the Ivy Book Shop’s JHU Press Night on November 11, from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. The event at the popular independent book store in north Baltimore is free and open to the public, and refreshments will be served.

Meet some of the Press’s local authors and get a jump on holiday shopping at the Ivy Book Shop’s JHU Press Night on November 11, from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. The event at the popular independent book store in north Baltimore is free and open to the public, and refreshments will be served.  More than a dozen JHU Press authors will be on hand to meet guests and sign books, including: Gil Sandler (Home Front Baltimore); Cindy Kelly (Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore); Mike Gesker (The Orioles Encyclopedia); Charley Mitchell (Maryland Voices of the Civil War); Michael Olesker(The Colts’ Baltimore); Fraser Smith (Here Lies Jim Crow); Bryan MacKay (Baltimore Trails); Ed Papenfuse (Maryland State Archives Atlas of Historic Maps of Maryland); Frank Mondimore and Patrick Kelly (Borderline Personality Disorder); Sara and Jeff Palmer (When Your Spouse Has a Stroke); Dinah Miller, Annette Hanson, and Steve Daviss (Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work).

More than a dozen JHU Press authors will be on hand to meet guests and sign books, including: Gil Sandler (Home Front Baltimore); Cindy Kelly (Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore); Mike Gesker (The Orioles Encyclopedia); Charley Mitchell (Maryland Voices of the Civil War); Michael Olesker(The Colts’ Baltimore); Fraser Smith (Here Lies Jim Crow); Bryan MacKay (Baltimore Trails); Ed Papenfuse (Maryland State Archives Atlas of Historic Maps of Maryland); Frank Mondimore and Patrick Kelly (Borderline Personality Disorder); Sara and Jeff Palmer (When Your Spouse Has a Stroke); Dinah Miller, Annette Hanson, and Steve Daviss (Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work). The Ivy Book Shop is located at 6080 Falls Road, in the Lake Falls Village shopping center at Falls Road and Lake Avenue in Baltimore.

For more information, call The Ivy Book Shop at 410-377-2966.

Friday, November 04, 2011

Tell Me.... an Ethical Dilemma

Sam is young man is applying for a summer program, a real resume builder. Among other things, the application asks if he has been treated for a psychiatric disorder. In fact, he's seen a therapist and he's felt anxious at times. His internist gave him some Lexapro samples and he feels better. The symptoms of his problems have been limited to his own subjective distress. His anxiety is not something that has disabled him, in fact he has not missed a day of school in 3 years -- and then for the flu-- he sees his therapist on the weekends, and no one would know he's been uncomfortable unless he told them. He's never been in a hospital, he's ultra-reliable, and he has great grades and extracurriculars. Any way you look at it, Sam is an energetic guy on the road to success.

Sam is young man is applying for a summer program, a real resume builder. Among other things, the application asks if he has been treated for a psychiatric disorder. In fact, he's seen a therapist and he's felt anxious at times. His internist gave him some Lexapro samples and he feels better. The symptoms of his problems have been limited to his own subjective distress. His anxiety is not something that has disabled him, in fact he has not missed a day of school in 3 years -- and then for the flu-- he sees his therapist on the weekends, and no one would know he's been uncomfortable unless he told them. He's never been in a hospital, he's ultra-reliable, and he has great grades and extracurriculars. Any way you look at it, Sam is an energetic guy on the road to success.What should he write on the form? It's a yes/no check box, no questions or place to clarify, so if he says yes, well, that could mean he has some subjective anxiety, or it could mean he has attention deficit problems, or it could mean he has been hospitalized 6 times after becoming violent, or has a severe mental illness. He's worried that his anxiety will throw him into a subset of applicants that the committee would rather not deal with: why choose someone for a project who has a mental illness if another equally qualified applicant is available without this issue to address?

Sam's mother say he should check "yes." He has been in treatment and he has a diagnosis and he takes a medicine. He has a psychiatric disorder and he needs to be honest.

Sam's father says that the question defies the spirit of what the committee wants to know. They want to know, Dad presumes, if there will be issues or problems or things they might need to accommodate, and there is no reason to believe that Sam's problem will interfere with his ability to negotiate life in a competitive or stressful environment. Sam, he contends, does not belong in the same category as someone who has attempted suicide, been hospitalized, missed work, or behaved in a disruptive or dysfunctional manner. If anything, Sam's anxiety drives him to focus and achieve and to be very conscientious. He's not ill, his father says, he's just more anxious on a spectrum of normal anxiety.

I want to know why forms get to ask such questions and put people in the awkward situation of having to answer something that is none of anyone's business versus being dishonest. It seems that if someone wants to know this, it might be asked in terms of "Do you have any health issues that might require any special accommodation?" Is there a limit to what random forms can ask and whether you're behaving unethically if you choose not to answer their questions or answer it less then completely? Sam tried leaving the question blank, but the computer wouldn't let him submit the form without checking all the boxes first. Can they ask if you have deviant sexual fantasies? If you've ever committed a crime (regardless of whether you've been charged or convicted)? If you say provocative things on your blog?

Thursday, November 03, 2011

I Still Don't Need To Talk

Three years ago in a post called I Don't Need to Talk I blogged about the evidence for and against critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) for preventing PTSD. Back then I suggested that CISD should not be mandatory for people who experience trauma for two reasons: most people don't develop PTSD after trauma and get better on their own even without therapy, and there was increasing evidence to suggest that CISD may make some people worse.

Today a story came across my Twitter feed (thanks USMCShrink!) about the medical response to the Japanese tsunami. Apparently psychological debriefing was strongly discouraged by Japanese mental health authorities for the reasons I just mentioned.

I think this is the leading indicator that attitudes are changing toward the role of psychiatry in disaster response preparedness. It also may mean that we might have to change how we approach the mental health care of veterans. I've talked to a lot of vets who were required to go through post-deployment debriefing. Did it help? Did it hurt? Are we doing the right thing? While treatment should be offered to people who really do develop disorders, in this case preventive intervention may not be so preventive.

Today a story came across my Twitter feed (thanks USMCShrink!) about the medical response to the Japanese tsunami. Apparently psychological debriefing was strongly discouraged by Japanese mental health authorities for the reasons I just mentioned.

I think this is the leading indicator that attitudes are changing toward the role of psychiatry in disaster response preparedness. It also may mean that we might have to change how we approach the mental health care of veterans. I've talked to a lot of vets who were required to go through post-deployment debriefing. Did it help? Did it hurt? Are we doing the right thing? While treatment should be offered to people who really do develop disorders, in this case preventive intervention may not be so preventive.

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

Privacy, Please?

Anon commented on my last blog post about clinical uses for Siri on my new iPhone:

The issue of clinical information is something I hadn't thought about. I downloaded an app yesterday specifically for GoogleDocs, and it imported all my documents. We wrote our book on this, so every chapter and every revision is now accessible on my phone, not to mention my posts for Clinical Psychiatry News and an unpublished novel or two. I downloaded the app so I would have the option to dictate patient notes. This would leave clinical information potentially accessible via a cloud or on the phone. I'm not sure it's all that interesting. My notes are usually pretty boring. But I did think that I would print them and then delete, rather than have to deal with keeping charts in order in cyberspace.

I guess I find it interesting that people worry about issues of confidentiality with total strangers in places where it's hard to imagine a use for what is likely to be pretty boring information. On the other hand, we live in a world where electronic medical records now exist in all types of venues. I work at a large hospital. I can access the records of any patient seen there, and if I go to a physician there, his notes about me will go onto the EMR. At this juncture, outpatient psychiatry notes are not on the EMR, just a record of the fact of the appointment (which does say "community psychiatry," and the psychiatrists add their medications, but this will change soon, I'm sure, and psych notes may well be part of the hospital's coming new system. The patients are not asked, and the doctors they see have access to all records without getting prior permission. There are very specific rules about whose records a healthcare worker may look at, and people have been fired for looking at their neighbor's records, but someone has to catch you. This means that a patient would have to ask someone with access to the system to see who had accessed their records, realize that one of those people was not someone involved with their care (Hey, that's my new boyfriend!) and then complain to the hospital and initiate some type of complaint (I think). There is nothing inherent in the system that prevents one person from looking at the medical records of their coworkers, boss, ex-husband, or even their doctors, aside from their own conscience and the fear of being caught (and reprimanded). At this point, and for this reason, I have chosen not to get care at the institution where I work.

Our state is also working on a system, called CRISP, that lifts medical records from all providers to a centralized system. You can opt out, but you don't need to opt in: do nothing and your healthcare information goes in. I opted out, and I got a letter telling me they would keep my information in case I changed my mind. Wait, so presumably my doctor will be feeding my information into this cloud, without asking my permission? I don't really know how this will work-- from the shrink standpoint-- because no one has contacted me about putting my professional records into this system, and since my records are all handwritten on hard copy charts, I don't know how this would play out.

Somehow we've come to think that electronic medical records will mean better care. I could be wrong, but I'm not really sure why we think that. It seems to me that the burden this will place on the physician to attend to the devices and the demands of this type of documentation, will consume time and detract from time with the patient. As is, I've noted it takes about 5 times as long to send an e-script as it does to write a prescription, starting with the fact that the e-system my hospital uses logs me out every 7 minutes. I'm told this can't be modified, and I'm not aware of any doctor who sees patients faster than every 7 minutes. Secondly, an electronic system is only as good as the information it propagates, and I've seen lots of mistakes in the electronic medical records. The internist notes that the patient is seen by psychiatry and takes Restoril. Wait, my patient is taking Restoril? I didn't know this..oh, I think he meant Risperdal. By my calculation, the number of lives saved by electronic information that is provided when the patient can't provide it himself, will about equal the catastrophes from the propagation of incorrect information.

So I should be worried that Apple can see my contacts? My brother, who is an original Caltech computer geek, told me recently that since I have a webcam, it's possible that someone could hack my computer and watch me through my camera. At first, I was alarmed at the possibility, but then I thought about this for a moment and said, "Why would someone want to watch me type?" Nothing that exciting is happening here. Sometimes I don't wear makeup, here and there I stick out my tongue and lick my lips, and okay, in front of the computer, when I'm writing, I kind of talk to myself. If this might interest someone...

I seem to have my own list of things to worry about. That someone might hunt my patient information out from the cloud just hasn't yet made my list.

"From the details in your contacts, it knows your friends, family, boss, and coworkers. "I find it kind of interesting what people worry about. I have hundreds of contacts in my phone. My husband is labeled no differently than my co-workers, than my friends. than my patients. I'm not sure what it means to have one's iPhone "fall into the wrong hands." I live in Maryland, so I'm not sure what Apple in Cupertino would do with my information, maybe send iPhone advertisements to my contacts?

That was from Apple's web site, regarding Siri. If you are using Siri for clinical purposes, know that Siri tells Apple everything. Siri--usly, how do you protect patient confidentiality if Siri/Apple knows so much? Sure, paper files can be stolen, so can cell phones. E files are vulnerable to all sorts of breaches. But what would you do if your iphone 4S fell into the wrong hands with all that clinical related stuff on it? Not quite the same as asking Siri where the closest dry cleaner is.

The issue of clinical information is something I hadn't thought about. I downloaded an app yesterday specifically for GoogleDocs, and it imported all my documents. We wrote our book on this, so every chapter and every revision is now accessible on my phone, not to mention my posts for Clinical Psychiatry News and an unpublished novel or two. I downloaded the app so I would have the option to dictate patient notes. This would leave clinical information potentially accessible via a cloud or on the phone. I'm not sure it's all that interesting. My notes are usually pretty boring. But I did think that I would print them and then delete, rather than have to deal with keeping charts in order in cyberspace.

I guess I find it interesting that people worry about issues of confidentiality with total strangers in places where it's hard to imagine a use for what is likely to be pretty boring information. On the other hand, we live in a world where electronic medical records now exist in all types of venues. I work at a large hospital. I can access the records of any patient seen there, and if I go to a physician there, his notes about me will go onto the EMR. At this juncture, outpatient psychiatry notes are not on the EMR, just a record of the fact of the appointment (which does say "community psychiatry," and the psychiatrists add their medications, but this will change soon, I'm sure, and psych notes may well be part of the hospital's coming new system. The patients are not asked, and the doctors they see have access to all records without getting prior permission. There are very specific rules about whose records a healthcare worker may look at, and people have been fired for looking at their neighbor's records, but someone has to catch you. This means that a patient would have to ask someone with access to the system to see who had accessed their records, realize that one of those people was not someone involved with their care (Hey, that's my new boyfriend!) and then complain to the hospital and initiate some type of complaint (I think). There is nothing inherent in the system that prevents one person from looking at the medical records of their coworkers, boss, ex-husband, or even their doctors, aside from their own conscience and the fear of being caught (and reprimanded). At this point, and for this reason, I have chosen not to get care at the institution where I work.

Our state is also working on a system, called CRISP, that lifts medical records from all providers to a centralized system. You can opt out, but you don't need to opt in: do nothing and your healthcare information goes in. I opted out, and I got a letter telling me they would keep my information in case I changed my mind. Wait, so presumably my doctor will be feeding my information into this cloud, without asking my permission? I don't really know how this will work-- from the shrink standpoint-- because no one has contacted me about putting my professional records into this system, and since my records are all handwritten on hard copy charts, I don't know how this would play out.

Somehow we've come to think that electronic medical records will mean better care. I could be wrong, but I'm not really sure why we think that. It seems to me that the burden this will place on the physician to attend to the devices and the demands of this type of documentation, will consume time and detract from time with the patient. As is, I've noted it takes about 5 times as long to send an e-script as it does to write a prescription, starting with the fact that the e-system my hospital uses logs me out every 7 minutes. I'm told this can't be modified, and I'm not aware of any doctor who sees patients faster than every 7 minutes. Secondly, an electronic system is only as good as the information it propagates, and I've seen lots of mistakes in the electronic medical records. The internist notes that the patient is seen by psychiatry and takes Restoril. Wait, my patient is taking Restoril? I didn't know this..oh, I think he meant Risperdal. By my calculation, the number of lives saved by electronic information that is provided when the patient can't provide it himself, will about equal the catastrophes from the propagation of incorrect information.

So I should be worried that Apple can see my contacts? My brother, who is an original Caltech computer geek, told me recently that since I have a webcam, it's possible that someone could hack my computer and watch me through my camera. At first, I was alarmed at the possibility, but then I thought about this for a moment and said, "Why would someone want to watch me type?" Nothing that exciting is happening here. Sometimes I don't wear makeup, here and there I stick out my tongue and lick my lips, and okay, in front of the computer, when I'm writing, I kind of talk to myself. If this might interest someone...

I seem to have my own list of things to worry about. That someone might hunt my patient information out from the cloud just hasn't yet made my list.

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

How Does Siri Help the Mental Health Clinician?

Next week, it will be my turn to write our article for the Clinical Psychiatry News website. Over there, we try to have our writing more specifically aimed at an audience of psychiatrists. I'm going to be writing an article on Siri and the Psychiatrist....in honor of my new iPhone 4s and the "personal assistant" function named Siri. Okay, I'm obsessed. Everyday, I find new things it can help me with. Today, I asked it, "What's the meaning of life." What, you don't ask your cell phone the finer existential questions? Siri answered, "All available evidence suggests chocolate." Wow! How old is Liza Minelli? 65 years, 7 months, 20 days. Calculate a tip? No problem. Convert Celius to Fahrenheit? A cinch. And she takes dictation. "Siri, please text Pt A 'Your lab results are fine.'" "Siri, please email Jesse, 'Will you write a new guest post for Shrink Rap?' " Okay, Siri flubs on this....I can't get her to learn that it's Shrink Rap and not Wrap. I downloaded a Google Documents App so I can dictate....patient notes, my memoir, a few novels, a Shrink Rap post here and there, To Do lists for Roy.... I think I'm set.

So, I'd like your help. What useful things are you doing with Siri? How has your iPhone made life as a clinician better?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)