Dinah, ClinkShrink, & Roy produce Shrink Rap: a blog by Psychiatrists for Psychiatrists, interested bystanders are also welcome. A place to talk; no one has to listen.

Monday, March 05, 2012

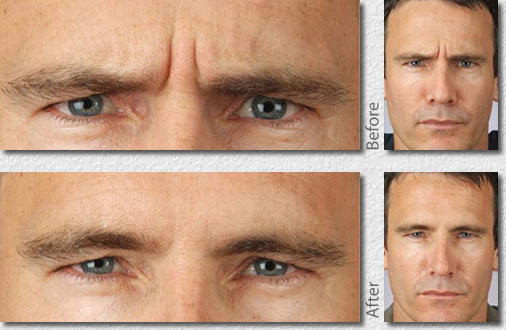

Does Botox Change The Shrink?

So I'm a little older than I used to be and recently when I look in the mirror, I've noticed some lines in my forehead when I make specific expressions. I'm not so sure I like them; when they show up in photos, they definitely make me look older. And yet, I know that these lines aren't just from aging, they are an occupational hazard. Part of attentive listening in psychotherapy involves using your face to convey, in non-verbal ways, obviously, feelings and expressions and interest and even questions. These are my quizzical lines. Really? Don't you think you're kidding yourself there? Give me a break. Not a word gets uttered, but oh so much gets communicated in silence, with the movement of just a few muscles. Yes, Clink, here and there I have a moment of silence. A short moment, but still. Wrinkles as an occupational hazard.

Every now and then I have the thought that maybe I should Botox those lines away, but my first thought is always, will it interfere with my work? Who am I as a psychiatrist without the Quizzical Look? Will my patients relate to me differently? Will they have worse/different/better therapeutic outcomes if my facial muscles are paralyzed? Oh, and since they came from my work, can I tax deduct the cost of botox treatments?

No worries, I'll stay wrinkled....or quizzical....as long as Clink continues to be a nun look-a-like and Roy remains a geek.

Saturday, January 22, 2011

This Medicine Might Kill You, But....

We all believe in Informed Consent and ClinkShrink likes to write about it. See Is It Malpractice to Lie...or better yet, read our book when it comes out where Clink talks all about the history of Informed Consent and many other such things. And one of the things people get angry at doctors for (? and shrinks in particular?) is when they have side effects or adverse reactions, and the doctor hadn't told them this might happen. People seem to get really mad about this, especially on blogs or on anti-psychiatry sites (sorry, no links here, find your own anti-psychiatry sites).

So I've wondered, does it matter if a patient is forewarned that they may get a side effect? There are many icky responses people have to meds, some are not very common, and sometimes it's hard to tell if it's the medicine causing the problem. And side effects can be uncomfortable, are they less uncomfortable if you were forewarned? You need a procedure and they make you sign a form saying that you know you could get an infection, hemorrhage, or die. Everyone has to sign or no procedure. If something bad happens, you can still sue, but if you're dead, you're dead. It's become so rote that it almost lacks meaning.

I do tell people about the more common side effects of medications. The pharmacist gives them a longer list. Google has it all for the curious, and I certainly don't discourage Googling, I sometimes suggest it. But I've wondered, does informed consent change things? Here's what my non-scientific observations have revealed.

There a medication that is associated with a rash that can be fatal. I tell people this, and the precautions they need to take to avoid croaking---slow titration, stop med/call if there is any rash at all. A shrink friend prescribed the medication to a patient who had a rare ?never heard of reaction and ended up in an ICU with liver toxicity and nearly died. The patient didn't die, made a full recovery, but the shrink was pretty traumatized and said she wouldn't use the medication again. After my friend's patient had this problem, I told every patient I prescribed this medication to this story. No one flinches. No one has said, "I don't want to take that medication that nearly killed someone." On the other hand, if I say, "This medication is associated with weight gain in some people," the resistance becomes huge. Even though weight gain is gradual and can be monitored, and I tell people they must get weighed twice a week and we can stop the medication if their weight increases by 4 pounds (that's my non-scientific cutoff for beyond the realm of fluid fluctuations). And I know skinny people who take lithium and zyprexa and stay skinny; not everyone gains weight. And I know people who feel so much better that they are willing to tolerate some weight gain.

Just my thoughts this chilly Saturday morning. By all means, tell us your stories.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Pharmaceuticals in the Information Age--Guest Blogger Dr. Mitchell Newmark

Look, I found Mitch, a classmate of mine from medical school, when he started to follow me on Twitter. Only I don't tweet (or I don't "emit tweets?" Sometimes I squawk, does that count?). I sent an email and while we were catching up, I invited Mitch to be a guest blogger.

Pharmaceuticals in the Information Age

It’s become a standard for me, when prescribing psychiatric medication, to ask patients if they intend to look it up on the internet. I think the internet is often a terrible place to go hunting for information. Either you’ll find a company sponsored site with happy faces, bells and whistles, or you’ll find disgruntled groups of patients denouncing the evils of one pill or another. The “impartial information” sites are frequently as toxic, especially for anxious patients, who can read through a comprehensive list of side effects, with little reference to their frequency or importance. And who knows if the information you’re finding is up to date? If a patient is paying to see me, it would make sense to bring his or her worries (Will my hair fall out?), concerns (Will this make me gain weight?) and fears (My friend took this and had a terrible reaction!) to me, not to the Web. If patients do want to Google their Rx’s, I ask them to send me whatever information they find which disturbs them. At least I can try to address the questions the internet has raised.

Even worse are television commercials for medications, which are unavoidable. I find that I need to watch at least some network TV just to keep up with what patients are seeing. How confusing to see such pained sufferers become spontaneously functional and cheery, while listening to the diabolical audio undercurrent of debilitating side effects. I know the messages are powerful; I frequently meet a new patient who comes in specifically because they saw a commercial for Abilify or Pristiq or something else during their favorite show. At least these drug mini-dramas do patients the courtesy of asking them to “ask their doctors.” Every patient is different; what works for someone, or causes side effects for someone else, is often an unknown. I find commercials send the message that THIS medicine will fix everyone.

Mitchell Newmark, M.D. is a psychiatrist, living and working in Manhattan, who is both a psychotherapist and psychopharmacologist, with a subspecialty in addictions.

Friday, December 18, 2009

Do Generics Work as Well as Name Brands?

It's my first night of vacation! I saw my last patient today and then started pulling the pictures off the walls in anticipation of my move. I ran over to see the new place, and it still needs insulation (it's on the floor), paint, and carpet. And doorknobs might be nice.

So we're expecting quite the snowstorm here. I'll let you know how it goes tomorrow, but the current forecast is for up to 20 inches. It didn't take me long to float from the weather to the health section of the New York Times, and here's an article by Leslie Alderman about generics versus name brands.

Are generics as good as name brands? I don't have any studies, I'm purely running on anecdotes, but this is my thinking: Usually. When I was resident, I learned that 15% of the time (and this isn't science, I don't think, I believe it's someone else's anecdote) generic nortryptiline doesn't work when name brand Pamelor does. So I've always asked patients to start with Pamelor....I don't use it much anymore....because who wants to spend 6-8 weeks on a medication trial and have someone not respond only to realize they were in that small group of patients who are sensitive to the brand.

Other meds: I've had a handful of people complain about generic Prozac-- fluoxetine. It's not as effective for them, or they have more side effects. Alderman's article talks about Wellbutrin XL and I didn't even realize that the XL form now has a generic. Sometimes people want the name brand.

So what do I do when a patient specifically requests the name brand? I give it to them: if they are right, then they are right. And if they simply believe that they won't respond to the generic, because there are people who say "Generics don't work on me," well, then there's power to such beliefs, and I just want my patients to get better.

What do you think?

Sunday, October 11, 2009

You May Go Now.

I've learned something important from....reading the comments posted to our blog, listening to people talk, being a person who talks....No one likes to feel their concerns are being dismissed (myself included).

It's a recurrent theme in the comments that are sent to us, especially with regard to medications: a reader has a concern about a medication, feels it isn't working or that the side effects are too severe, and either their doctor does not address their concerns in a way that feels validating or the reader perceives that the doctor does not understand....since I'm not there, I can't say which is happening, but the feeling on the part of our readers is clear.

And just so you know, I've been on both ends of the discussion. I once lowered the dose of a medication, found it to be just as effective at a very low dose, and was told this was a "homeopathic dose." I didn't really know what that meant. In my terms, I had a headache that felt very real to me, and after taking a very low dose of a painkiller, my headache was gone. I wanted the least possible medication, so I stuck with the low dose. I'm not sure what was meant by the comment, but I heard it as the dose I was taking was so low it couldn't really be helping and I must have been imagining it's efficacy. This was my interpretation; the doctor may well have said it was simply to comment on how low the dose of medication was and not as a statement related to either the realness of my symptom or the realness of my response. I suppose I would have preferred to have heard that I must be rather sensitive to the effects of the medication, the "homeopathic dose" comment rubbed me the wrong way.

I've learned there a patients who have unpredictable and unexpected responses to medications. Some people tolerate huge doses of medications, others don't tolerate even small doses. Sometimes people have weird responses, and we don't really know what to make of it. My favorite example of this happened many years ago-- a patient told me he saw "trails" of light when he turned his head which he attributed to the Serzone I prescribed. Okay, that's weird, I'd never heard of that type of side effect from ANY medication. I didn't know what to make of it. The next week, I saw a case report in a journal of three cases of "visual trails" induced by Serzone. Go figure.

So why don't doctors just take patients' word when they say they are having a specific symptom: be it from an illness or from a medication? Why don't doctors hear when patients say they are very sensitive or not and need very high or very low doses of medications? More and more, I think we do.

Why not always?

Here are some reasons:

--Sometimes doctors are dumb.

--Sometimes doctors are egotistical.

--Sometimes doctors are frustrated. Especially if a medication helps an illness but causes awful side effects. And it's not just doctors. Family members will want patients to stay on their medications because they are less irritable, more functional, easier to get along with...even though the medicines cause side effects.

--Sometimes patients lie. This is especially true when controlled substances are involved: So a patient says that he's anxious and absolutely the only thing that helps is 6 mg a day of Xanax and he feels slighted that the doctor doesn't just take it at face value and prescribe it. Or believe that he's dropped the pills down the sink? Or never gotten them from his 90 day mail order company

--Some people are very suggestible and develop many side effects that they've read about. I really do wish there was a way of saying this without the word "suggestible" having a pejorative feel. Can't it just be? In medical school, I once heard someone say you can tell if a patient is simply saying "yes" to everything if they said their hair hurts when they pee (hair can't feel).

--Sometimes patients complain of things we've just never heard of .happening before. I don't think these problems should be dismissed, and I've taken to telling patients that I'm not in their body/head and they really need to be the one to determine if the benefit from the medication outweighs the side effects. This can be a difficult decision in the time while they are waiting to see if the medication is going to be effective.

--Sometimes patients misinterpret their doctor's comments. I'm often told I think such-and-such when in fact I don't think that at all. My doc might be surprised to hear I took the "homeopathic" comment to mean any thing other than 'my, what a low dose you responded to."

Finally, I've learned that patients can have very high expectations of their doctors. People often write in angry that their docs didn't warn them about specific side effects, and they'll mention a side effect to a medication I've never even heard of. It doesn't mean I don't think it happened, it just means it's not the usual for a psychiatrist to warn a patient, hey MedX could make your nose turn green and swell.

I think in psychiatry, we're all still just finding ourselves. So many of these medications are so new, and they efficacy and side effects varies so very much from person to person. Why does one patient get better with no side effects at all from the very first medication, while someone else is on maximum doses of 5 medicines at once, and still another patient has intolerable side effects to a tiny dose of anything?

Monday, February 16, 2009

The SSRI Horse Race-- Take Our (Meaningless) Polls

This is not science, I'm just playing here, nothing random, nothing controlled, just questions for our readers.

I just read Peter Kramer's Psychology Today blog post called Lexapro and Zoloft in a Cloud of Dust. Dr. Kramer talks about the relative efficacy of SSRI's, their market share, and if the drug company's influence docs to prescribe in a way that isn't in sync with research. Lexapro, the most expensive SSRI, apparently has the biggest market with 13% of the market share. He writes:

Now comes news of a large-scale analysis of research on antidepressant efficacy. Published in The Lancet, it finds a hierarchy, with Remeron, Zoloft, Effexor, and, yes, Lexapro, leading the pack, Cymbalta and Prozac in the middle, and Luvox, Paxil, and (especially) reboxetine, which is marketed outside the US, bringing up the rear. Celexa and Wellbutrin gave statistically fuzzy efficacy results; the two drugs appeared to be about average for the group. In terms of tolerability, Zoloft, Lexapro, Celexa, and Wellbutrin led the pack. So the results give a special place to Zoloft and Lexapro.

Do read the original post.

So I thought I'd put up two polls, and again, this isn't science, it's just curiosity. Pretend you didn't read the paragraph above, and I'd like you to answer two questions: What do you think is the most Effective SSRI, and Which SSRI do you think causes the most side effects. I don't care if you're the patient or the doctor, or a non-MD therapist who's simply just heard patients talk about the meds. It's a question of perception, with the awareness that maybe you haven't seen all the horses race. Efficacy: Which med works the best (If you've only been on Prozac and that worked great, it's fine to answer that!). Side Effects: Which med makes people feel the yuckiest (now there's a scientific term).

Thursday, November 13, 2008

It Could Happen To You, Too

ClinkShrink and Roy would like me to shut up already. One more thought, and then I will, I promise. I know, I'm getting everyone stirred up about the question of whether docs respect when patients say they have side effects from meds. It's an issue that's come up over and over on Shrink Rap.

So Anonymous (one of the many) wrote as a comment:

Maybe if psychiatrists put themselves on meds as this doctor did with Wellbutrin, your perspective would change. After she suffered horrific side effects and withdrawal symptoms, she is a lot more empathetic when her patients complain about side effects.

Thank you, Anonymous, for the comment-- it's a topic I've been wanting to write about for a long time and you've provided a spring board.

So when people have a problem or a solution, it's normal to think that other people might have the same reactions. Many of the anti-anti-depressant (or anti-AnyDrug) comments on the internet have the overtone that these medicines hurt me, they should be banned, or no one should take them. I'm an offender: if you tell me you have back pain, I'll be the first to ramble about how my back spasms have been totally cured by swimming (sub-text: swimming might fix you, too).

Psych meds: They work for some people. They don't work for some people. Some people have side effects. Some people don't. It's quite clear that many people simply don't tolerate them. And I do believe that some docs don't 'believe' their patients when they describe unusual side effects or reactions or that they may believe the patient but respond in a way that feels dismissive to the patient. I also know that I sometimes wonder if a side effect is from a medication or from something else (another illness, another medication, something else going on at the same time) . I see a fair number of people who return and say "I didn't like how I felt and I stopped taking that stuff" and usually that means that trial of that particular medication is over. I also see a fair number of people who say medication helps and they've had no side effects from it, at all. Or medication doesn't help and they have no side effects from it-- it's feels like they are taking a sugar pill.

So the idea that shrinks should try taking an antidepressant so they can empathize with the patient's response -- there is one important assumption here: That the shrink would have side effects! What if the doc, any given doc, goes on Wellbutrin like the doc in the article and unlike that doc, doesn't have any side effects? By this logic, wouldn't that make them less empathic? Huh, that stuff is hell on you, can't be, I tried it myself and I was fine. By the same token, if the doc pops a pill and has awful side effects, might the doc never be willing to give it to anyone? After all, it caused awful things to happen, and might the doc therefore deny a certain treatment to his patients who might benefit from it? I think such things happen all the time: doctors are human, it's hard to ignore your own experiences, especially the extreme ones.

I'll shut up now.

Monday, November 10, 2008

Quote of the Day

I've decided, instead, that I liked the remark posted by blogging psychiatrist Doug Bremmer in the comment section of my post Tell Your Doctor if You Experience Any of the Following....

He writes:

I do often feel when I read our comments from readers who've had bad experiences with medications or hospitalizations or psychiatrists who say insensitive things, that people feel there is something purposeful about it. It's hard when someone comes in and describes something as a side effect of the medication and I recall that the symptom was there before the medication was even started. With time, we've learned that this can be the case-- if a patient starting an SSRI now says "this medication is making me feel more suicidal," Docs listen. It's still hard when someone says a medicine causes a side effect never described and I don't know what to do with it. Sometimes I try to talk people into staying on their medication if, for example, they complain that a newly added anti-depressant is making them more depressed-- the medicines take time to work, weeks in fact. If a patient continues to complain, eventually I'm left to conclude that this medication either doesn't work or isn't tolerated in this person. Sometimes people complain bitterly about side effects while at the same time they say they feel the medication helps, and then I say: It's up to you. It gets trying when this means that every visit consists of stopping a medication that hasn't been given a fair chance only to begin another medication-- the arsenal of medications available can be run through pretty quickly with this strategy and it doesn't make sense. Okay, I'm rambling.

Sunday, November 09, 2008

Tell Your Doctor If You Experience Any Of The Following...

A reader writes in:

I might suggest that in some cases, the more outre side effects of SSRIs are not reported because the person taking the drug is afraid of being thought insane. I had unbelievable rage while I was taking Effexor, and never told anyone about it because I was afraid of not being believed, and also afraid that there was something else seriously wrong with me.

I am a highly intelligent and naturally moral person, and never hurt anyone despite my desire to do so, though I did put my fist through a wall at one point. But I had extremely disturbing violent impulses while on the drug, including a desire to maim or kill my beloved cats, and a strong desire to physically assault the woman I was dating at the time. All of this vanished completely when I decided to voluntarily go off the drugs, which I had been told I would need for the rest of my life. As it happened, the psycho-emotional disorder I had was consistently missed by therapists and clinicians, and SSRI drugs were not an appropriate treatment.

This may or may not account for the peculiar side effects, but at any rate -- my thought is that possibly these things go unreported due to shame and fear on the part of the patient.

So we don't give medical advise here on Shrink Rap. I borrowed this comment, however, because I'm struck with how often patients withhold critical information. If a patient tells me that since we started a medication, he's had a new symptom, if that symptom is intolerable to him, or in any way worrisome, I don't sit there thinking they are crazy. I stop the medicine. If the side effect sounds like it's a little uncomfortable but the overall quality of someone's life is better with the medication, I simply restate the facts and my thoughts about whether the good outweighs the bad, I let the patient chime in with their thoughts (I'm not in their body), and I consider the circumstances before the medication was started as well as the response to the medicine. If someone was suicidally depressed and unable to function , then maybe it's worth tolerating a dry mouth in exchange for the ability to return to work and not be sad or suicidal?

It's not just medications-- it's anything major going on in someone's life. If something huge is going on in a patient's life, the doctor needs to know. "I'm more depressed lately," has one meaning in the context of a medication change and another meaning in the setting of a recent loss.

What psychiatrists can't do is know what someone is experiencing without being told. We don't have crystal balls, we don't have ESP, we aren't mind readers, we don't "know" what you're thinking, feeling, worrying about, distressed by, unless a patient tells us in fairly precise terms.

Monday, September 08, 2008

What Didn't I Tell You?

It's not specific to psychiatry, but this caught my eye, first in the Wall Street Journal, and then through their link in the Boston Globe.

So a woman in her 70's is getting chemotherapy. She is also on painkillers and complains to her doc that she's dizzy. Fourteen times. She then has a car accident and kills two people. The relative of one of the people who was killed sues the doctor who prescribed her medications for failing to tell her not to drive. The claim is that if the doctor had specifically told her not to drive, she wouldn't have. A similar case went to court last year.

I don't know the details of the case, it's just what I read in the on-line articles, and we all know the press sometimes presents things in interesting ways. The question gets to be, however, what exactly is the doctor responsible for when a medication is prescribed? Side effects may or may not happen: bottles are labeled by the pharmacy, should everyone be pre-emptively told not to drive? And once some does have a side effect, and knows they have it, is it still the physician's responsibility to state the obvious: you're sick, you're on a sedating medication, it's making you dizzy, don't drive or operate heavy equipment? Is it the physician's responsibility to even ask if the patient drives, or to absolutely ascertain that he doesn't? Is saying "don't drive" enough? Should the family be brought in and the keys be taken away? What about the not as obvious: the doctor never said to give up gymnastics on the balance beam. Or not to rock climb (...ClinkShrink!) which may be hazardous, meds or not.

So the striking thing about this story is that the suit wasn't filed by the patient, but by the survivor of the victim's behavior. So, like, if an engineer takes a medication and has an accident, can the family members of every one injured on the train sue the doctor who prescribed the medication that the engineer took? And what about the pharmacy? It's all kind of confusing.

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Is It Worth It?

Okay, so Judith Warner has a neat post on the New York Times Domestic Disturbances blog where she talks about The Migraine Diet, food, meds, and lifestyle issues pertaining to the treatment of her migraines. She talks about the recommendations of David Bucholz, the Hopkins migraine Guru (and my neighbor...) -- avoidance of medications that can lead to rebound headaches and a diet devoid of...food (--I'm kidding of course, but apparently caffeine, pizza, beer, and chocolate--the foods Shrink Rappers love-- are out). Ms. Warner writes:

Some people do manage, through diet and exercise, or by protecting themselves from their worst “triggers,” to free themselves from their drugs. But many can’t do it. Many find they can’t accept living in the compromised condition that drug-free existence requires.A smart high school girl I know switched a few years ago from a mainstream school, where she was struggling with dyslexia and ADHD, to a school that specializes in teaching kids with severe learning disabilities. Being there has permitted her to function without her ADHD meds. But now she’s bored. She’s dispirited by the lack of academic challenge and she wants out, because she’s afraid that, without academic challenges, she won’t be able to get into a mainstream college.

That’s the tradeoff: taking daily drugs, or living a life that feels not quite worth living.

The story ends with a prescription for Topamax and a snickers bar, result pending.

-------------

If you haven't been following Foo Foo's blog, Turn Your Head and Scoff, by all means, visit. He tells a moving story about a young woman's death from colon cancer-- I started to comment, but just didn't know what to say. He tells about life in San Diego with the fires burning, and of course, there are those lovely pics he posts of the interior of his own GI tract.

I think the Red Sox will clinch it tonight.

Monday, September 24, 2007

How to Select an Antidepressant: Part 2

Dinah posted about How Psychiatrists Select Antidepressants, which was a very thoughtful and concise description of the factors we take into consideration. Supremacy Claus commented on Dinah's pragmatic, plain-speaking distillation (talk about plain-speaking pragmatism, check out this legal eagle's excellent blog). Dr Smak (another great blog... she and Dinah should go shoe-shopping together) was surprised to find no mysterious revelations, and "The" Shrink (a great new psychiatrist blog... welcome!) felt doctor preference was a missing element.

I started a comment, but it got so long and non-plain-speaking (sorry, S. Claus) that I moved it here.

Shrink, not so sure about the physician preference part (or maybe I am atypical... ha). I don't have a "favorite" or fall back antidepressant, as I find that when I apply Dinah's list (which is quite comprehensive and a good list), I am usually left with one or a couple drugs, and can still find a reason to pick one over the other (eg, cost). I feel I am quite familiar with the zillions (ok, maybe it's only 15 or 20) and ready to pick whichever seems best.

I do think Dinah's #4, 5, and 6 should be expanded on, and #4 should be split into 2 separate sections (I'm a splitter)... #4a being Other Medical Issues (eg, Seizure -x-> Wellbutrin; Psoriasis -x-> Lithium; Hypertension -x-> Effexor; etc) and #4b being Drug Interactions.

Drug Interactions is a whole 'nother post, and is a BIG factor for me when prescribing. Many of my pts are on multiple meds, so it becomes really important to think about this. Prozac and Paxil, for example, are famous for 2D6 interactions, so I avoid it when folks are on drugs which are solely metabolized by that enzyme. Luvox is a great hs antidepressant, but will muck with 1A2-metabolized drugs. Serzone and 3A4 drugs (though, haven't seen Serzone in years now... too bad, was a great drug to have around, esp if you knew how to use it... great for blocking SSRI-induced sexual side effects).

#5: Target Sx - When I think thru these, I think in terms of receptors (may be a tomato-tomahto thing here). I hear "no appetite" and think "I want histamine antagonism"; I hear "can't concentrate" and think "dopamine agonism"; I hear "no energy" and think "norepinephrine".

#6: Side Effect Profile - This is the one I spend the most time on with a pt. For any given side effect that is either desireable (sleepy, energizing, stimulates appetite, reduces appetite, etc) or undesireable (weight gain, wt loss, sexual, rash, seizure, nausea, etc), I have a pecking order in my head of drugs and their propensity to cause -- or not cause -- the particular side effect (other term is "adverse reaction", though they are only "adverse" when undesireable). The above 3 sections are where a better understanding of psychopharmacogenetics would come in handy.

The above may be where Dr Smak noted the perceived "secret way" in which shrinks pick 'em. What may be different in the way in which psychiatrists and PCPs select antidepressants is just in the way these thought processes get all merged together, or maybe thought about in an explicit way (my receptor-tomahto approach) or an implicit or nonverbal way (Dinah's best guess-tomato approach).

This "gut feeling" about which drug to use is merely the end result of a massive probability calculation which is automatically performed in the brain, based on all the above input about which side effects or target symptoms should take precedence for that specific pt, which drugs are more or less likely to deliver them based on receptor and metabolic profiles and based on literature and personal experience, in addition to the other factors like likelihood for compliance and affordability, all boiled down to a single "I think you should try Effexor". Much of that calculation is not conscious, and I think Dinah belies the complexity under the surface by simply (but honestly) stating "my best guess".

Sunday, September 23, 2007

How A Shrink Picks An Anti-Depressant

Midwife With A Knife wants to know how a psychiatrist chooses a medication for an SSRI-naive patient. Wow, I'd already started that post when she asked.

So a patient comes for treatment. His symptoms meet criteria for Major Depression, no question here, and he wants medication to help his condition. This is his first visit to see me.

Wellbutrin Remeron Serzone Pamelor Elavil Nardil Parnate Emsam Trazodone

I probably missed a few.

So how does a shrink decide what medicine to begin?

1) Past history of response. If the patient says, Oh, yeah, six years ago I felt this way, I took Paxil for six months and that helped a lot and I didn't have any side effects, then Paxil it is.

The path changes if the story is that the medication didn't work or had side effects.

2) Family history of response. This is the patient's first episode, but mom swears by Wellbutrin, it's helped her when nothing else would. This would be a good first choice.

3) Patient preference. He's here because his best friend took Celexa and became a new and wonderful person. I have no idea what friend's diagnosis is or why Celexa was chosen for friend, but if there isn't a contra-indication, then I might as well honor a patient's wishes and there's some power to believing something will help. Similarly, if patient reports that Celexa caused best friend to commit outrageous acts of horror and he wants anything but Celexa, I pick something else.

4) Other Medical Issues. I don't start with meds that interact with what the patient's already on. I don't pick meds that might exacerbate an existing medical condition. Wellbutrin is contra-indicated in patients with seizure disorders, eating disorders, or a history of CNS lesions, so I don't start with it in these patients. I save the risky stuff for after we've been at it a while, and then only with a fair amount of discussion about possible risks compared to possible benefits.

5) My Best Guess at What Will Help the Target Symptoms. Patient is tired and unmotivated...Wellbutrin is reportedly a bit energizing, so maybe that's what I use. Patient also has a lot of OCD symptoms, I might go with an SSRI. If someone has a concurrent pain syndrome, Cymbalta or a TCA might be my first choice.

6) My Best Guess at the Side Effect Profile, for better or for worse. Really, this is a guess. I actually hate this issue because patients often worry about side effects they never get, but okay, if someone is agitated, I might start something I think of as being more calming. If someone says they'll die if they gain a single pound, I pick something more weight neutral.

7) The Patient's Financial Concerns and What I have Samples of. This is only a consideration if the patient is uninsured and paying cash for the meds, but this is not a trivial thing. After that, I move to What's Cheapest that will work and won't cause intolerable side effects. If the patient has been on something and had good success, then loses their insurance, I might try something cheaper in the same class of meds, but I wouldn't recommend a switch from say a working SSRI to a cheap Tricylic-- it's not worth the risk.

Can I say a word about Weight Gain as a side effect? Some patients refuse any medication that's been associated with this. But clearly, and I'm probably repeating myself at this point, there are people who don't gain weight on medicines that are said to cause weight gain, just like there are people who don't get better with anti-anythings. People respond to meds differently. My suggestion to those who are concerned they'll gain weight-- if there's some reason to believe a medicine might help, it may be worth a try. Buy a scale. Get weighed before starting the medication. Get weighed every 2-3 days after starting it. If you gain 5 pounds (1 or 2 or 3 can be variations in fluid retention or scale flakiness), Then it's worth worrying about weight gain and addressing whether it makes sense to continue.

We've been at this blog so long, I've lost track of what I've said already, what I've thought about saying, what I want to say.

Monday, June 25, 2007

My Three Shrinks Podcast 26: Black Box Reloaded

June 24, 2007: #26 Black Box Reloaded

Topics include:

- Side Effects of Psychotherapy. Sharon Begley from Newsweek wrote an article entitled, "Get Shrunk at Your Own Risk." We discuss this particularly in reference to grief and bereavement, PTSD, and CISD.

- Discussion at Cheryl Fuller's Jung at Heart about therapy as a treatment for an illness vs. as a tool to improve one's life. And here's an afterthought.

- The Impact of the FDA's SSRI Black Box on the Decline in Depression Treatment in Kids. We discuss the June 2007 AJP article by Libby et al. showing that there was a 58% drop in expected number of antidepressant prescriptions for this population after the black boxes went up, and that the proportion of depressed children who remained untreated with antidepressants increased some three-fold. Other data has showed an increase in the suicide rate if this population afterwards. In the graph below, the black line represents the percentage of kids with major depression who were prescribed no antidepressant.

- Q&A: "In my neck of the woods there is pretty much NO 'talk' therapy in short term inpatient settings. I know of many depressed individuals who have decompensated in these settings, and have had their depression actually increase on their departure. Any thoughts?"

| Find show notes with links at: http://mythreeshrinks.com/. The address to send us your Q&A's is there, as well. This podcast is available on iTunes (feel free to post a review) or as an RSS feed. You can also listen to or download the .mp3 or the MPEG-4 file from mythreeshrinks.com. Thank you for listening. |

Saturday, May 26, 2007

Depakote & Ammonia

This is a brief post about the underrecognized side effect of elevated serum ammonia (NH3) levels causing altered mental status, confusion, and delirium in people taking valproic acid or valproate (Depakene is US brand name... also applies to divalproex sodium, or Depakote).

A case of Depakote-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy was presented at last week's Annual APA meeting. Here's another case (actually, this one is mostly valproic acid toxicity) on Erik Mattison's blog. This problem is often not recognized because ammonia levels are not standard blood tests to do (this test is also a bit of a pain, in that the blood has to be kept on ice immediately after drawing it).

In his presentation on May 21st, Dr. Rasimas discussed the case of a 36-year-old with treatment-resistant schizoaffective disorder and quiescent hepatitis C who returned to the emergency department in a state of lethargy and confusion less than 3 weeks after being hospitalised for lithium toxicity. Personnel in the ER started the man on sodium divalproex, which is chemically related to valproic acid, at a dosage of 1000 mg in the interim to treat hypomania. A nightly dosage ultimately resulted in a serum level of 114 mcg/mL...Typical symptoms for this type of metabolic encephalopathy include confusion, agitation, disorientation, insomnia, hallucinations, picking at bedclothes or in the air, twitching, and asterixis (also called "liver flap", where your hands twitch when holding your arms outstretched as if you were stopping traffic). If an EEG is performed, this usually demonstrates a diffuse encephalopathy.

When the patient was admitted to the hospital, his AST and ALT were normal at levels of 17 U/L and 44 U/L, respectively, while ammonia was elevated at 66 mcg N/dL. Serum lithium was 1.2 mmol/L.

Dr. Rasimas said he was asked to consult on the case, at which time he determined that the patient's dose of sodium divalproex should be immediately discontinued, suspecting a case of hepatotoxicity. The patient's other psychotropic medications, including lithium, were then resumed. Lactulose and supportive care were given. Ammonia peaked at 111 mcg N/dl within 36 hours of presentation while AST and ALT never exceeded 38 U/L and 81 U/L, respectively.

The symptoms of delirium resolved slowly during the 96 hours following the discontinuation of divalproex sodium.

I've seen several cases of this, and it is gratifying to recognize it, stop the Depakote, add lactulose (helps to reduce the ammonia), and see improvement. I've seen it with even lower ammonia levels (40's) when GI docs say that they doubt that is the problem. But when it improves, it is hard to think that it is anything else.

Sunday, April 08, 2007

FDA Drugs: January 2007

FDA Drugs: January 2007

- Vynase (now Vyvanse) gets approvable letter: New River Pharm and Shire are poised to release a new ADHD drug, lisdexamfetamine (was NRP-104).

- Generic Wellbutrin XL approved: by Anchen Pharma.

- Wellbutrin Package Insert was modified: to reflect the following additional info regarding its use in people with renal failure: "An inter-study comparison between normal subjects and patients with end-stage renal failure demonstrated that the parent drug Cmax and AUC values were comparable in the 2 groups, whereas the hydroxybupropion and threohydrobupropion metabolites had a 2.3- and 2.8-fold increase, respectively, in AUC for patients with end-stage renal failure." Also added was mention of double vision and increased intraocular pressure as reported adverse reactions.

- FDA releases Guidance on Pharmacogenetic data. The FDA released definitions for genomic biomarkers, pharmacogenomics, and pharmacogenetics.

- Alexza is working on Schizophrenia Agitation drug: The drug is an inhaled form of loxapine, a typical antipsychotic.

- New Antidepressant: Pristiq. Wyeth, who makes Effexor XR (venlafaxine), received an approvable letter for Pristiq (desvenlafaxine succinate), which is a metabolic derivative of Effexor; both drugs are serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Approvable letters have conditions which must be met before the product can be marketed. The Wyeth facility in Puerto Rico must pass FDA's muster, and the marketing plan must be approved, prior to its release for the Major Depression indication. Wyeth is also going after an indication for Vaso-Motor Symptoms (VMS) related to menopause ("hot flashes" in English).

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Medicines: The Good, The Bad, & The Ugly

I work in Free Society -- a term I learned from ClinkShrink who works in the jails. My patients are all adults and with few exceptions, they seek my help of their own accord. Often they come with a request for medications, sometimes a request for a specific medication--something that's helped them in the past, something that's helped a friend.

So humor me while I talk a little about medicines.

The Good

Medications are prescribed by doctors to target symptoms, to target abnormal laboratory or radiologic findings, or to prevent the development of disease in at-risk populations. Symptoms are things like pain, insomnia, hallucinations, cough, angina, heartburn. The goal of medication is to relieve the symptoms. Abnormal laboratory values are things like elevated glucose levels in diabetics, low red blood cell counts (anemia), elevated cholesterol. Examples of medication given to healthy people might include aspirin to prevent heart attacks, or the ill-fated Hormone Replacement Therapies that were given to women in the hopes of preventing heart disease and

osteoporosis, Lithium for bipolar disorder that is continued between symptomatic episodes. I didn't get it all-- fit chemotherapy for cancers, anti-hypertensives, and a slew of other medications where you will. At any rate, the point of the medicine is to get rid of something bad or to prevent something worse from happening, or both: anti-hypertensives normalize blood pressure and prevent end-organ damage --end organs for high blood pressure are the retina, the kidneys, the coronary arteries, and the cerebral arteries-- so the goal of them medicines is to normalize the numbers and prevent strokes, blindness, and renal failure.

So the good: medications sometimes work. In some people, some of the time, they make the bad things go away and they allow people to live healthier lives longer.

The Bad:

The bad thing about some medications is that they have Side Effects. Side Effects are results of the medications that are nearly always unwanted, kind of the weeds in the garden. Symptoms in their own right, they happen, with some regularity, and sometimes we even use medications for their side effects rather than their primary purpose. So trazodone is an antidepressant, but it makes a lot of people sleepy, so it's used in sub-therapeutic (for depression) doses to help with insomnia. Mostly, though, side effects are bad-- they are uncomfortable for the patient and are often a reason people will stop medications. It's great if that medicine strengthens my bones so I won't break them later, but not if it gives me intolerable Side Effect X now. Side Effects are uncomfortable, they aren't fatal, and they are reversible, they go away when the medication is stopped, and for certain medications, certain side effects are fairly common-- if Ibuprofen upsets your stomach, you're not alone.

What's interesting about side effects is that few of them happen to everyone. So a lot of people will have sexual side effects from SSRI's, but certainly not everyone. Some people will have a tremor from lithium, some will get tired on thorazine. Certain cancer chemo therapies cause everyone to lose their hair, and dry mouth on therapeutic doses of tricyclic antidepressants (at least in my personal observation) seems to be par for the course, but many side effects seem to be fairly random. Many psychotropic medications are known to cause weight gain, and that has been a topic of concern in the comments on Shrink Rap, but I've certainly seen plenty of people take medications that are associated with weight gain who never gain weight. We don't know who will have side effects, kind of like we don't know who any given medication will work for, and because of this, it really becomes impossible to tell patients anything more than a list of the more frequent side effects with this implicit understanding that other side effects may also occur. Pharmacies provide lists, but it's hard to be comprehensive. From the doctor standpoint, there is no guarenteed free ride: when you swallow a pill the possibility of a side effects are there and largely unknown. For the patient who is struggling with a condition that's impeding his life, as many psychiatric patients are, it may be worth taking the risk of any given side effect because that side effect may simply not happen. Since weight gain is a hot topic, I will say that I've seen patients have good responses to Lithium, Clozapine, and Zyprexa (all notorious for causing weight gain) who've not gained an ounce. Other's have inflated like balloons-- the only good news here is that the weight goes on a pound at a time and the medicine can be stopped if the weight starts going on. The problem, of course, is what to do when the patient has a good response to the medicine but also has side effects: unfortunately this scenario leaves the patient with difficult choices.

The Ugly:

Side effects are unpleasant, but often anticipated, and reversible. Many medications have really rare and really ugly effects-- these aren't side effects but Adverse Reactions. They can be awful, and they can be fatal and they can be irreversible. So Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, fulminate liver failure, and agranulocytosis are not side effects, they are life-threatening adverse reactions. Tardive Dyskinesia is an Adverse Reaction, though one that takes time to develop. Adverse reactions are the stuff of Black Box Warnings. The usual response to the Ugly is to stop the medication ASAP.

So what do I tell patients?

Mostly, I tell patients the more common side effects and of any black box warnings. I don't know, off hand, every side effect of every medication. If a patient asks in more detail, I open a PDR and read from the list of side effects. I offer reassurance that the medication can be stopped if side effects develop. I can offer no real guarantees about the possibility of catastrophic reactions-- though generally these are less then the risk of getting into one's car and usually I'm left to say "I've never seen that." A friend recently had a patient experience a life-threatening really rare reaction to a medication (one not listed in the PDR) and for a while after I told any patient I started on that medication about this patient's reaction--- no one refused the medication even after hearing the story. My friend says she will never again be able to prescribe that medication. Rational? No, but our own experiences are sometimes more powerful than statistics. In the case of side effects, ultimately the patient is left to decide if the cure is worse than the disease. In the case of an adverse reaction, I stop the medication and don't restart it.

Sometimes, in some patients, the medications simply relieve the symptoms without any ill effects. It's nice when that happens.

Sunday, December 10, 2006

My Three Shrinks Podcast 2: Roots

We'd like to thank our readers and listeners for your kind comments and suggestions about our first podcast. This one's a bit longer, at about 33 minutes. I think we'll get better about the time. About 20 minutes seems to be a good balance.

This is actually the second half of the original podcast, which went long so we sliced it into two podcasts. Don't expect to get a podcast every other day... if we do one every other week, I'll be pleasantly surprised (though I'm striving for every Sunday). Maybe we can be like Digg's Kevin Rose and Alex Albrecht and drink alcohol at the beginning of each podcast... that would be interesting.

Here are the show notes for the podcast:

December 10, 2006: Roots

Topics include:- Dr Anonymous is again not mentioned in this podcast (but we do thank him for the idea about the musical bumpers between topics)

- Thorazine Immunity: Clink reviews a 1992 case in which a prisoner sued the on-call psychiatrist for involuntarily medicating him with chlorpromazine due to violent, self-injurious behavior... but without going through any hearing panels for forced meds [Federal Code: Civil action for deprivation of rights]

- Dinah brings a duck to the "Shrink Rap Studio" (my kitchen table)

- FDA hearing on December 13 about adding a black boxed warning on antidepressant labels about the possibility of increased suicidality in adults: Will this reduce access to these drugs, causing undertreatment of depression and actually INCREASE suicide rates? (Check here for background materials)

- Recent PubMed articles and Corpus Callosum post about this whole antidepressants and suicide issue. Also, Dinah mentioned this, hot-off-the-press, Finnish article, showing an increase risk of attempts and a decreased risk of deaths.

- Treatment of social phobia [PubMed]

- Social phobia and alcohol [PubMed]

- Paxil- and other SSRI-related withdrawal symptoms [PubMed]

- Sexual dysfunction and SSRIs [PubMed]

- Putting roots on someone

- Psilocybin mushrooms for Monk's OCD

- Maryland psychologists discuss adoptions in gay marriages

- NYT: Gender dysphoric children

This podcast is available on iTunes. You can also download the .mp3 or the MPEG-4 file from mythreeshrinks.com.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

FDA Drugs: Sept 2006

Just a quick list of relevant FDA and related notices...

Lamictal & Pregnancy: cleft lip in first trimester... see also Neurology abstract reviewing risk of fetal abnormalities in 4 anticonvulsants (note: take numbers with grain of salt... the N for each drug exposure is kinda low)

Generic Topamax released

Effexor label revised: mentions risk of serotonin syndrome with triptans

Abilify 7.5mg injectable: approved for agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

Contrave advances: New obesity drug... combines Wellbutin/bupropion and Revia/naltrexone to cause weight loss... 6-month trial in 250 people results in 7.5% wt loss (vs 1% for placebo). [see also Orexigen site]

Thursday, September 21, 2006

SSRI Antidepressants & Violence

There's an article over at PLoS Medicine about antidepressants that makes for interesting reading. The article, Antidepressants and Violence: Problems at the Interface of Medicine and Law by David Healy, Andrew Herxheimer, & David B. Menkes, reviews pharmaceutical company data regarding SSRI-induced violence, aggression, and hostility. The main antidepressant reviewed is paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat, others), though fluoxetine/Prozac, sertraline/Zoloft, and venlafaxine/Effexor XR, are mentioned.

The three authors acknowledge that they have all served as expert witnesses supporting and opposing the role of SSRI antidepressants, which makes the article seem a bit like an advertisement for their expert witness business. Nonetheless, the review of drug company data (mostly GSK) is worth a gander.

Roy: I found most interesting the low incidence of episodes of "hostility" among both those on drug or placebo. For example there were only 55 (0.4%) reports of "aggression" or "assault" in 13,741 adverse effect monitoring reports from the UK of paroxetine, and 1 report of "murder". I'll leave it to the reader to find incidence reports in the general population, but I'm guessing it is at least this or higher.

GlaxoSmithKline's data from all of their placebo-controlled paroxetine trials showed "hostility events" (which includes mere thoughts as well as actions) in a total of 60 out 9219 paroxetine cases (0.65%) and 20 out of 6455 placebo cases (0.31%). Statistically, one appears to be twice as likely to have an "hostility event" on Paxil than on placebo.

The lawyers are lining up at the courthouse for business (Clink, feel free to pick up on that one).

The article, which anyone can view in its entirety (that's what I like about PLoS Journals), includes 9 actual case examples or folks who did bad things, like robbery and murder, after taking SSRIs (sometimes after only 2 doses).

Clink:

There's a reason why this article was not published in a standard peer-reviewed journal. It seems like an article that can't make up it's mind about what to discuss. It didn't really address the legal issues involved in drug-related criminal prosecution and it's an incomplete discussion of the clinical studies. Frankly, I left the article feeling a little bothered by the lack of focus.

Regarding the clinical issues: violence is a multifactorial behavior, and I think it's overly simplistic to reduce it to a simple medication cause-and-effect. Confounding variables are the presence of personality disorders, previous acts of violence, active affective disorder symptoms and co-existing substance abuse. We know nothing about these confounding variables from this article. While clinical trial data will be useful to identify strong associations that could be attributed to medications (eg. weight gain, increases in prolactin levels) it is less useful for low base-rate phenomena like homicide. As Roy has already pointed out, base rates of general aggression were low to begin with in the clinical monitoring data from the UK.

Regarding the legal issues: that was actually the interesting part for me, and they totally glossed over it! They only presented their own small case series. They didn't discuss diminished capacity defenses, insanity or involuntary intoxication. To keep it simple (and to minimize the length of this post) I'm only going to talk about involuntary intoxication.

When it comes to mental health defenses in crime, all jurisdictions exclude voluntary intoxication as a defense. This is done for the obvious reason that the majority of violent offenses occur under the influence of drugs and alcohol, so social policy dictates that people must be held accountable for the consequences of their choice to abuse substances. However, longterm use of some substances can cause permanent mental changes long after the person is abstinent. PCP psychosis can persist for months after chronic abusers stop using. Longterm alcohol dependence can result in permanent memory deficits. These residuals problems can be used as the basis for a legal defense.

Another legal theory that allows for substance abuse is the idea of involuntary intoxication---what I think of as the "mickey" defense---meaning that you took something without knowing it. Drinking spiked punch or accidentally taking the wrong pill might be an involuntary intoxication. Having an unusual or rare reaction to a medication---like an SSRI---could be a type of involuntary intoxication defense. Something like this would be more common with other drugs, however, with the classic one being steroids. About 15% of people prescribed prednisone have a dose-dependent affective side effect. When the first case studies were published about the psychiatric effects of anabolic steroids there was a flurry of criminal defenses based on this. Later research showed that the people who were more prone to 'roid rage' where people who also had antisocial personality disorder.

The final issue you'll hear about is the idea of paradoxical intoxication, in which a person has an extreme reaction to a small quantity of a substance. Roy mentioned the cases of homicide or robbery after only two doses of an SSRI; this would be an example of proposed paradoxical intoxication defense. (Actually, the best example of paradoxical intoxication I've seen is the movie Final Analysis. It's also a good illustration of the kind of criminal defendants who propose defenses like this.)

So that's my input. Pass the Paxil and stand back!

Dinah:

What never fails to amaze me is not that people have side effects or adverse reactions to medications, but the great variety of responses people can have to the same medication. If 70% of people will have a given response to a medication (hmm, let's say dimunition or resolution of depressive symptoms if we want to look at the cheery side of things, or sexual dysfunction if we want to look at the gloomier), well what about the other 30% of folks? Why is it that some patients have a great clinical response and there is no down side? Some people seem to be more medication-sensitive in that they are more prone to side effects or need lower doses of medicines, but there isn't necessarily carry-through from one class of drugs to another. So, we all know that Lithium may cause weight gain, but I've seen patients on high doses of lithium for years that haven't gained any weight, and we all know that zyprexa may cause weight gain (note that I say "may" because it's just not a given), so why will the same patient might tolerate one of these with no problem, and start piling on the pounds when you switch to the other?

Roy's reference gives several explanations as to why SSRI's might induce violent behavior: switch to mania (perhaps with psychosis), akathesia, activation, emotional numbing. Clinically, the question of SSRI-induced suicidal/homicidal behavior has always been a tough one: these medications aren't prescribed to people who are trooping along Just Fine. Suicidality is a very common symptom of Depression and SSRI's are prescribed for depression; we're left wondering if the SSRI caused the suicidality, began working and lifted the patient to the point of being able to act on the thoughts, shifted the patient into a bipolar mixed state, or simply was ineffective in treating the depression and was incidental to the final act.

Given the vast range of odd side effects/adverse reactions that people get from medications, the studies linking suicidal ideas in children to SSRI's and the extreme nature of the cases discussed in the PlosJournal article, it's probably reasonable to say that a very small percentage of patients given SSRI's may become violent. Still a bit of a stretch for me, because there are also people who have no history of violence who unpredictably kill someone, and it becomes hard to look at the correlation to a medication when tens of millions of Americans take that medication (kind of like I eat Twinkies and I didn't kill anyone) and only a few of them unpredictably become violent.

And what does this mean clinically? I think I'm left to say something fairly flat, like: Not Much, So Far. I don't work with children, where I believe the implications are broader-- the black box warning on SSRI's regarding suicidality may be giving pediatricians a moment's pause before prescribing them, and the latest recommendations suggest that kids be seen fairly often for the first month of treatment: probably not a bad idea, though perhaps cumbersome given the shortage of child psychiatrists.

To date, I have not seen a previously nonviolent adult become violent on an SSRI. People still enter treatment asking for these medications, and many people find they effect life-altering changes for the better. Some people have no response at all. Some people feel much calmer, less irritable, and better able to cope with what life throws them. Some simply cease to be depressed and identify that the medication makes them feel like their old, pre-depressed self. Often, people have sexual side effects and are left to make a decision. If someone were to report violent ideas on the medication, as with any distressing side effect, I would discontinue it. For an out-patient practice, the decision to take or not to take medications is ultimately the patient's; I can discuss the possible risks and the possible benefits, I can make a recommendation based on studies I've read and patient responses I've witnessed, I can strongly encourage someone to take medications, and ultimately I suppose I could refuse to treat someone who I felt I couldn't help at all without medication, but the final decision is generally an issue of team work, and often the patient comes in predisposed: "I'm never taking meds" or "Prozac made my best friend better and I want some of that stuff."

The vignettes in this story are striking. To date, I've not felt a need to warn patients that they might become violent: these cases are the exception, not the rule, not anywhere close. If I hear enough of them, I'll start warning people, until then, I'll leave it to the ever-present media, and I'll keep a close eye on my patients.

As a "blogging doctor" I am struck by how much anger there is out there about side effects of antidepressant medications, and how much psychiatrists are felt to be to blame for that. Perhaps there has been over-promotion of prescription medications. But there are side effects that we don't know about and only learn about with longer experience. We are not magicians or mind readers.