Over in The New York Times, Melissa Miller has an article titled "How to Find the Right Therapist."

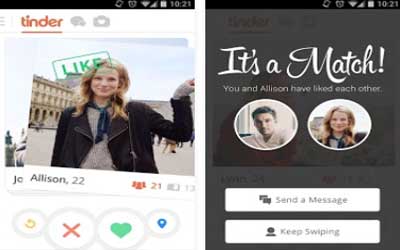

Miller compares it to dating, and she makes the very valid point that good chemistry helps, it's really nice to like and respect your psychotherapist, and to feel a sense of rapport. In psychotherapy, the talking is an integral part of the treatment and the relationship itself can be healing. So it is important in therapy that the patient be comfortable confiding in the therapist, be open and honest, and feel safe saying things that can make one feel vulnerable.

Miller compares it to dating, and talks about the pleasure of comparing wedding plans with her finally-found perfect therapist. She then offers advise on how you, too, can find a good therapist.

Her advise is awful. Really. It's not that some of her points aren't valid, but she starts by giving a quick summary of what type of professional you should see:

Determine the type of professional you need.

If you’re suffering from ailments like panic attacks, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder, look for a clinical psychologist or social worker rather than a psychiatrist, said Dr. David D. Burns, adjunct clinical professor emeritus at the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine.If the issue is something more like bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, sociopathy, borderline personality disorder or schizophrenia, it’s best to see a psychiatrist or a psychologist with considerable experience in that specialty

I don't know Dr. Burns, whom Miller quotes, but really? Don't see a psychiatrist for panic attacks, depression, PTSD, or OCD? But, hey, we apparently do a great job curing sociopathy! I don't get the division, and I'd suggest that all of those conditions are well-treated by psychiatrists (which may or may not include medications in the treatment).

Miller advises readers to check therapist reviews on-line. She doesn't point out that anyone can review anything and there is no way of knowing that good or bad reviews are not verified to be from patients and may be from best friends, ex-lovers, or even the therapist himself. I'd go for personal recommendations from doctors or known patients myself. And Miller proudly touts that she ghosts her eating disorder counselor and 'broke up' with her therapist by text. Hmmm.....

Do some research, she suggests, and it seems reasonable to check to make sure the therapist has reasonable credentials and hasn't been sanctioned by a licensing board for something egregious. A quick telephone discussion is also reasonable, but the author suggests asking the therapist what they like most about being a counselor. Again, really? Maybe stick to 'Do you have experience treating my problem.' I'm not sure it's best to start a relationship with a therapist by inquiring about their personal motives for going to work each day; much as I love my work, being asked what I like best about my work by a stranger looking for treatment might make me feel like a college student being asked that wonderful question of "where do you see yourself in 10 years."

She goes on to address issues of insurance participation and finances. She suggests that if it's too expensive that the patient should switch the sessions to once a month (not necessarily a bad idea, but shouldn't the therapist be consulted?) or use Skype or email for sessions -- and why would Skype be cheaper? And how would email work? She goes on to quote Michelle Katz, a nurse/health advocate:

“They become family to you, so you can ask them to work on a payment plan,” Ms. Katz said.“Anything is negotiable, and if a therapist is not willing to negotiate with you, especially after you’ve been with them for a while, it’s probably not a good match for you,” Ms. Katz said.

Finally, Miller talks about timelines for treatment and quotes Dr. Burns again:

“If my son or daughter were depressed, I’d want them to go to a

therapist who can get them dramatic improvements in just a few sessions,

not just have them pondering their life for months or years without

change,” he said.

Rapport is important; feeling cared about, feeling comfortable-- these are all good. Competency is also important, and Miller doesn't address this beyond a minimal level. She talks about looking for a therapist like looking for a date, and she assumes the date has no needs of his own: that every patient's a great catch who every therapist would be thrilled to have. But mental health care is often limited by huge demand, and therapists might not negotiate rates because they have mortgages, student loans, childcare, and food costs. It's a give and take -- skype and email sessions might not be in the patient's best interest or convenient for the therapist. And if you call my office, before you even know me, please don't quiz me on what I love best about my job. Just sayin'.

So finally, if you want my thoughts on how to find a psychiatrist, I'm going to link you back to an old Shrink Rap post:

http://psychiatrist-blog.blogspot.com/2010/10/how-to-find-psychiatrist.html