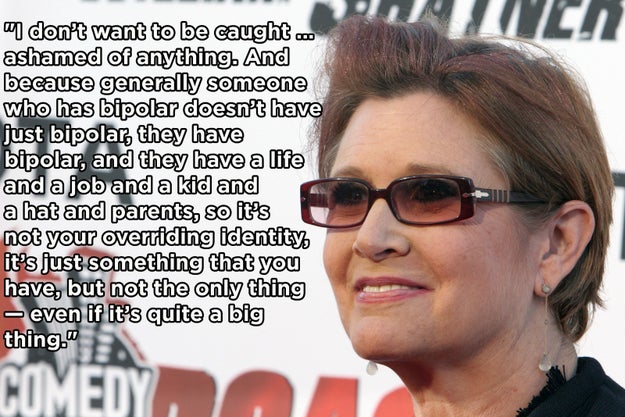

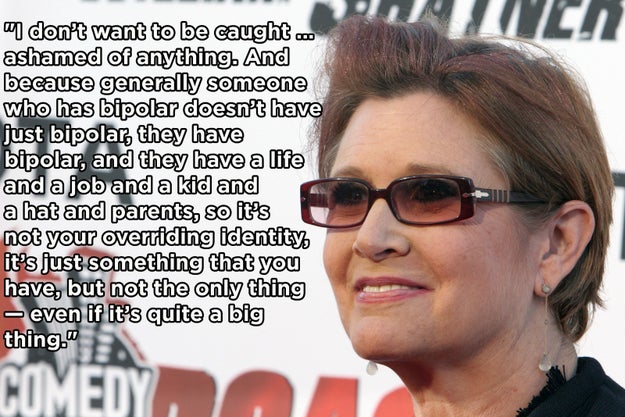

10. On not being defined by your mental illness:

Rene Macura / ASSOCIATED PRESS / Via bphope.com

This was my favorite of the 13 things. If you'd like to read them all on Buzzfeed, go Here.

Dinah, ClinkShrink, & Roy produce Shrink Rap: a blog by Psychiatrists for Psychiatrists, interested bystanders are also welcome. A place to talk; no one has to listen.

The book was a page-turner because of elegant structure and pacing. I really cared about the author’s take on things –because she is a psychiatrist? because I’ve followed her blog for a while?– which meant that I was interested in the protagonist’s thoughts, feelings and actions. At times I ached for the mess her life was in, at others I wanted to shake her into action, and then she’d find her backbone again, just in the nick.

I like to read all sorts of books, but books where there's something in it that reflects a part of me, a part of my life, a part of my experiences, are something I go out of my way to find. I have not found any fiction book that does nearly as much to show what psychotherapy is like.

I just finished this book, written by two people I am proud to call friends and colleagues, and one which highlights and tells the story of many of my other friends and colleagues, on all sides of the issue that the book covers. It is a marvel of balance and completeness, and of shared ideas and vigorous debate regarding differences in opinion. In a world that seems to be becoming increasingly polarized, this book is an object lesson in how to discuss contentious issues while still getting along.

None of us has a monopoly on "the truth" because in the area of involuntary treatment, there is no single, unitary "truth." I recall struggling as a psychiatry resident with issues of autonomy versus my rudimentary ideas about what would be "best" for a patient. I recall losing sleep - for patients I let go, and also, differently, and over a much, much longer term, for patients I may have wrongly retained.

This book forces the reader to confront issues related to self-direction, to the adverse impact of mental illness on decision-making, to the battles being fought over where the line is that should legally permit the involuntary treatment of a person who does not want it.

Buy it, and read it. You will learn much, and perhaps, just perhaps, get a sense of where the "other side" is coming from.

So often I write blog posts about topics I read about in the paper. I take a few quotes and expand upon them. Today I want to look at book review by Dr. Damon Tweedy, a psychiatrist at Duke University and author of Black Man in a White Coat: A Doctor's Reflection on Race and Medicine. Only this is a little different. Dr. Tweedy is reviewing a book that We wrote! And a fine job he did, if I do say so myself.

So often I write blog posts about topics I read about in the paper. I take a few quotes and expand upon them. Today I want to look at book review by Dr. Damon Tweedy, a psychiatrist at Duke University and author of Black Man in a White Coat: A Doctor's Reflection on Race and Medicine. Only this is a little different. Dr. Tweedy is reviewing a book that We wrote! And a fine job he did, if I do say so myself. So from the Washington Post, to appear in print tomorrow, Tweedy writes about

So from the Washington Post, to appear in print tomorrow, Tweedy writes aboutProponents of enforced treatment often point to horrific but rare events, like mass shootings, committed by people with mental illness. But psychosis alone is only a modest risk factor for violence. A 2009 study of more than 8,000 people with schizophrenia found that those who did not abuse drugs or alcohol were only slightly more likely than the general population to be violent.There are several studies that demonstrate that assisted outpatient treatment can reduce the risk of hospitalization, arrest, crime, victimization and violence. Few, however, are based on high-quality randomized controlled trials. A 2014 meta-analysis of three randomized-controlled studies of more than 700 people found no statistically significant benefit of enforced outpatient care in reducing hospitalizations, arrests, homelessness or improving quality of life.It can be devastating for families and doctors alike to watch psychosis seemingly claim the lives of those we love or care for. And in some situations, brief episodes of enforced inpatient or outpatient treatment may be necessary. But in my experience, weeklong inpatient stays, or yearlong outpatient treatment regimens, can do more harm than good when they engender distrust. Perhaps we must accept a new reality — to truly engage people in treatment we need to understand their own experience of psychosis and its treatment.